You are about to enter another dimension—not only of sight and sound, but of mind. A place where expectation meets interruption. Next stop: the classroom.

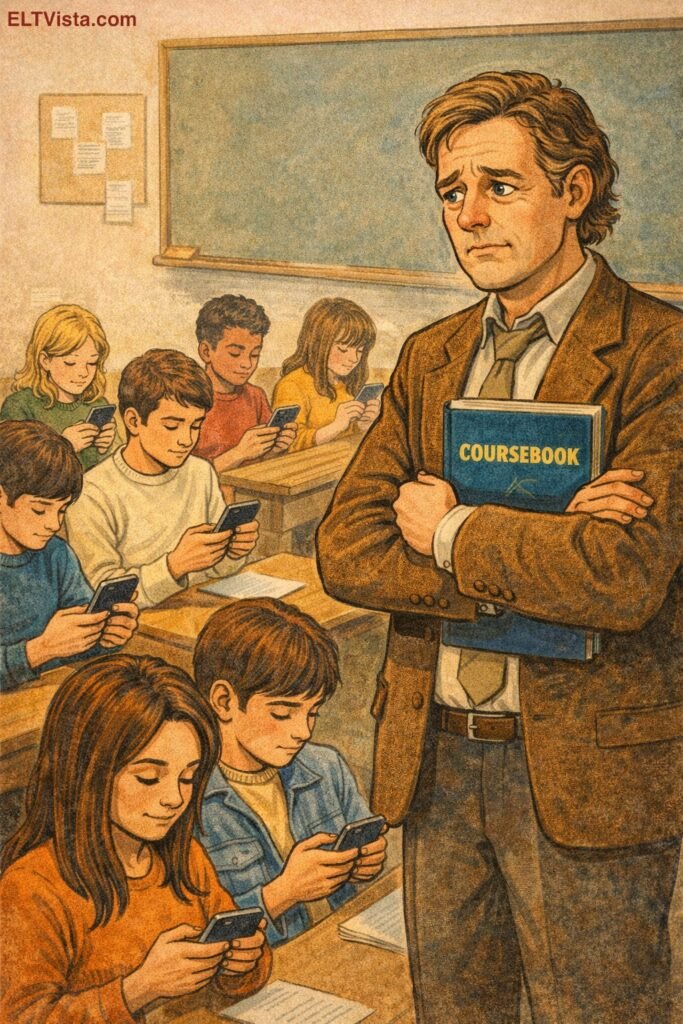

You are already in the middle of the lesson. The grammar point is unfolding exactly as planned. Examples sit on the board. Your explanation is measured and clear. Yet the room is drifting. You sense the disconnect and wandering eyes.

A glow from handheld screens. Fingers scrolling. A backpack unzipped. Someone whispering. Eyes moving everywhere except toward you. A bag of potato chips is opened.

Tensely, you pause, allowing the moment to correct itself, but it does not. You reach, almost instinctively, for imperative speech—the professional language of control many teachers have been conditioned to trust.

“Pay attention!”

Your intention is entirely sound. You want to teach. You want the class with you. You want your preparation —and your professionalism—to matter. You want respect. You demand respect. You are the authority.

The words land. The room quiets, at least on the surface. And yet, you sense that something still is missing. Students may comply, yet they are not fully present.

And you feel the added tension immediately, because beneath imperative speech lies something deeply human: the desire to be taken seriously and to know that your voice carries weight.

So it is worth asking, if only for a moment:

What are you hoping to do with the attention you are demanding? To move through the explanation? To secure the grammar point? Ensure the lesson proceeds as intended?

After all, learning does not occur simply because a room grows quiet. Students can obey an imperative without ever entering the thinking. Perhaps, then, the deeper question is not whether students are paying attention. Perhaps it is what makes attention possible in the first place.

When Language Shapes the Learning Climate

Decades ago, child psychologist and educator Haim Ginott offered a perspective that feels remarkably contemporary. His work on classroom communication suggested that the teacher’s language does far more than manage behavior; it establishes the emotional architecture in which learning either expands or contracts.

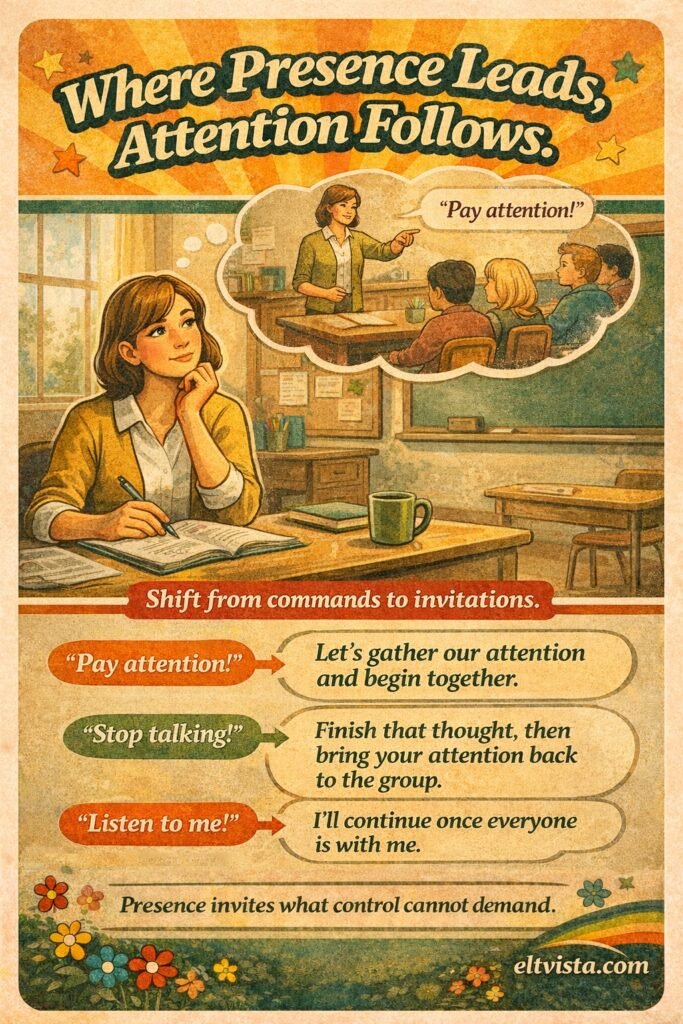

Ginott encouraged what he called congruent communication; it is professional language that preserves student dignity while guiding the classroom toward purpose.

The distinction is subtle but consequential. A command such as “Pay attention” centers control. It positions attention as something to be extracted.

However, a Ginott-informed alternative might sound quieter:

“I’ll begin once everyone is with me.”

The shift is not merely stylistic. It signals steadiness rather than struggle, presence rather than performance. Authority remains intact, yet it is exercised without escalating tension or inviting resistance.

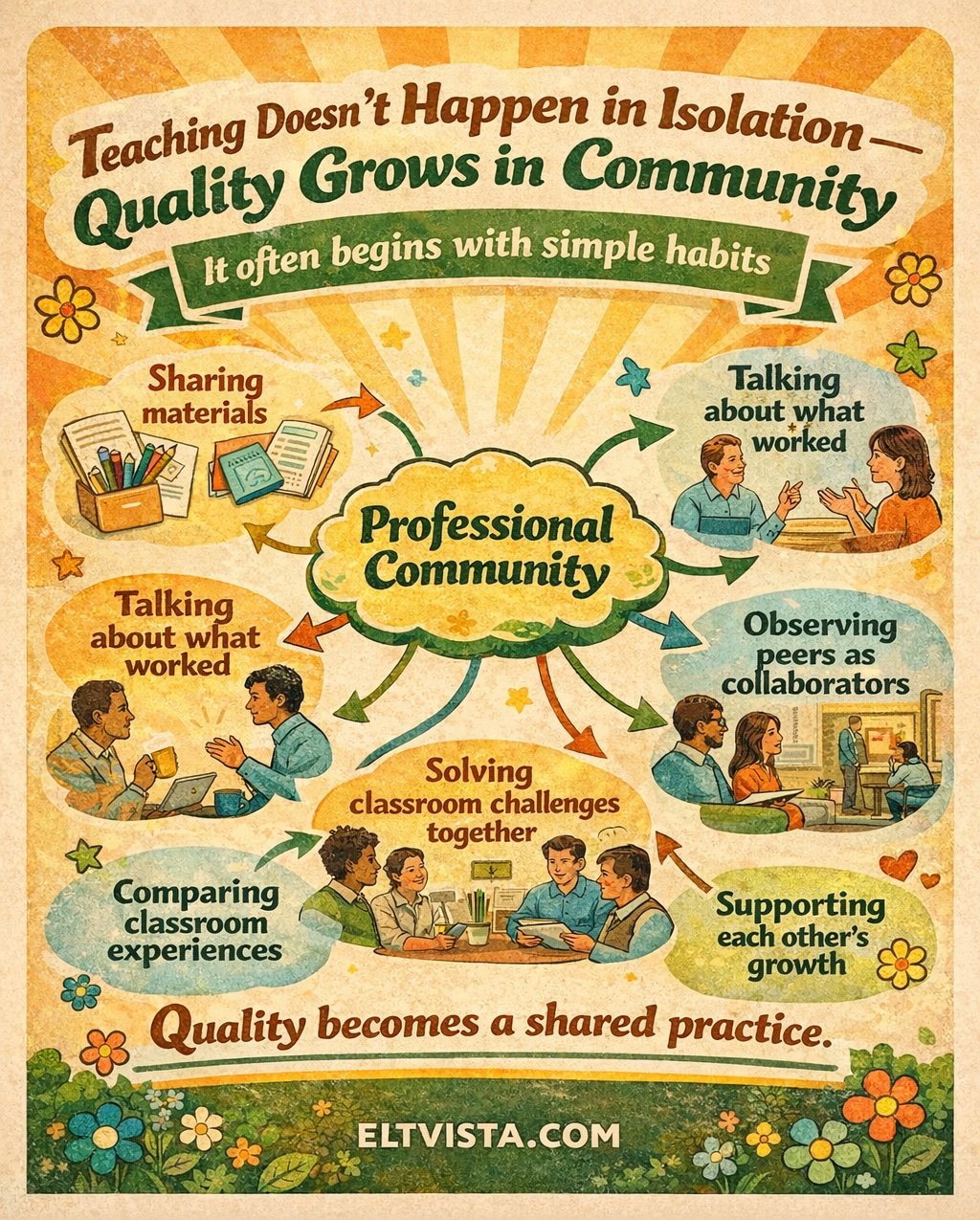

Seen through a broader humanistic lens, students are more likely to engage when they experience psychological safety and mutual regard. This is akin to one later echoed by thinkers such as Carl Rogers. Similarly, the sociocultural insights of Lev Vygotsky remind us that attention deepens when learners are positioned as participants in meaning-making rather than as subdued observers.

Attention, in this sense, is rarely commanded into existence. More often than not, it emerges when the classroom feels both structured and relationally secure.

This invites an important professional reflection: what many describe as classroom management may, in practice, be the visible expression of teacher presence.

Experienced educators tend to discover that presence reduces the need for imperatives. Students align not because they are compelled, but because the learning environment communicates coherence and purpose, and even safety, inclusion and acknowledgement—acknowledgment for what they as humans and participants in the process bring to the classroom.

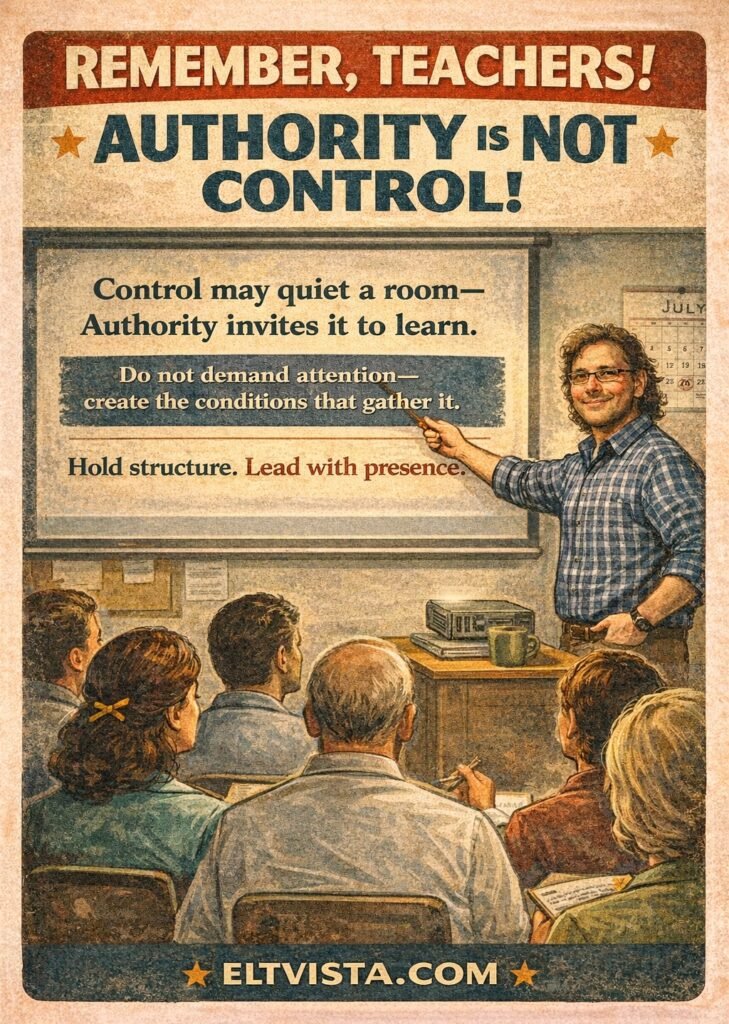

Authority Is Not Control

Moments of inattention often feel personal. When students disengage, the interruption can register as a quiet challenge to one’s professional standing—because it’s not just procedural, it’s existential. Such reactions are deeply human; teaching places the self visibly inside the work.

Ginott invites a different pause. Rather than reaching for imperative speech—language many of us inherited from older, compliance-driven models of schooling—we might ask how our words position students in relation to the learning itself.

Constructivist theory has long reminded us that learners engage through participation, not passive reception. Communicative language teaching (CLT) carries this forward: attention rarely holds through explanation alone; it strengthens when students use language, negotiate meaning, and recognize themselves as contributors, not just spectators.

Social-emotional learning points in the same direction. When the classroom feels psychologically steady and relationally secure, attention is less demanded than gathered around purpose.

Attention, then, is not the destination but the threshold. If it leads only to one-way presentation, it quickly thins. When it opens onto dialogue and shared thinking, it sustains itself and is inviting to learners.

Authority is not the same as control. Control can quiet a room; authority organizes it and facilitates engagement. Strong classrooms grow not from technique alone, but from a teacher’s capacity to hold structure and humanity in balance.

What About the Teacher?

Teachers, too, deserve a moment of reflection here.

When we ask for attention, what is guiding that request? Urgency to cover material? Desire for order? The understandable need to feel taken seriously? Or is it the intention to bring learners into meaningful encounter with ideas, language, and one another?

Professional language is never incidental. It reveals our assumptions about learners, about authority, and about the kind of community we hope to cultivate.

Ginott reminded us that dignity is not a pedagogical accessory; it is foundational to the emotional climate in which learning becomes possible.

In the end, students may forget the specific directive that began a lesson. However, they are far less likely to forget how the classroom felt—whether it was governed primarily by control, or guided by a presence that made attention feel both natural and worthwhile.

And perhaps that is the dimension that matters most—not simply what was taught, but the human space in which learning was invited.

While you are contemplating your personal and profesional development, please consider our self-paced 120-hour online certificate course to your list of teaching qualifications:

For more information, click here for the ELT Vista Certificate in Humanistic TESOL Teaching. Enrollment is now open with a special Holiday Launch promotion!