Not long ago, I wrote about the distinction between presence and authority in the classroom. The response to that piece suggested that many teachers recognize the tension instinctively. This article moves the conversation forward, because once we begin questioning authority, a larger question emerges: Where did our classroom habits come from in the first place?

Teachers inherit more than lesson plans and coursebooks. We inherit systems, expectations, and professional instincts that were shaped long before we entered the classroom. Some of these inheritances serve us well. Others remain simply because they have always been there—and what’s problematic to me is that this seems to be the only reason they continue to be embraced: they are venerable, sacrosanct, ossified, and fossilized.

Inherited Systems and Unexamined Traditions

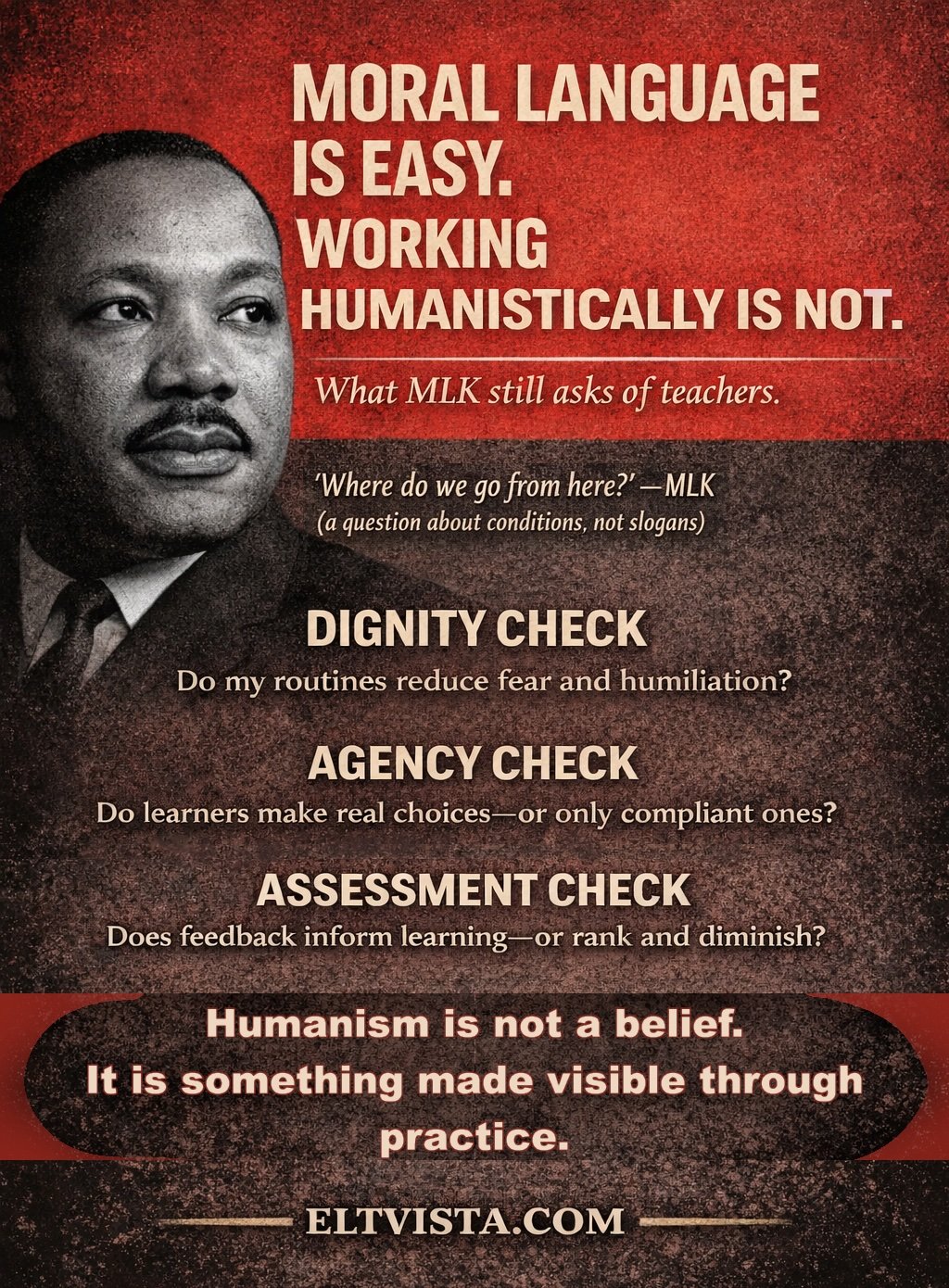

Here in the USA, Black History Month invites reflection on the ways societies inherit systems across generations. One of the most uncomfortable lessons from history is how easily harmful practices become normalized when they are repeated long enough. Behaviors that once seemed unquestionable can later appear unthinkable. Yet at the time, they were simply “the way things were done.”

Education has its own versions of this pattern.

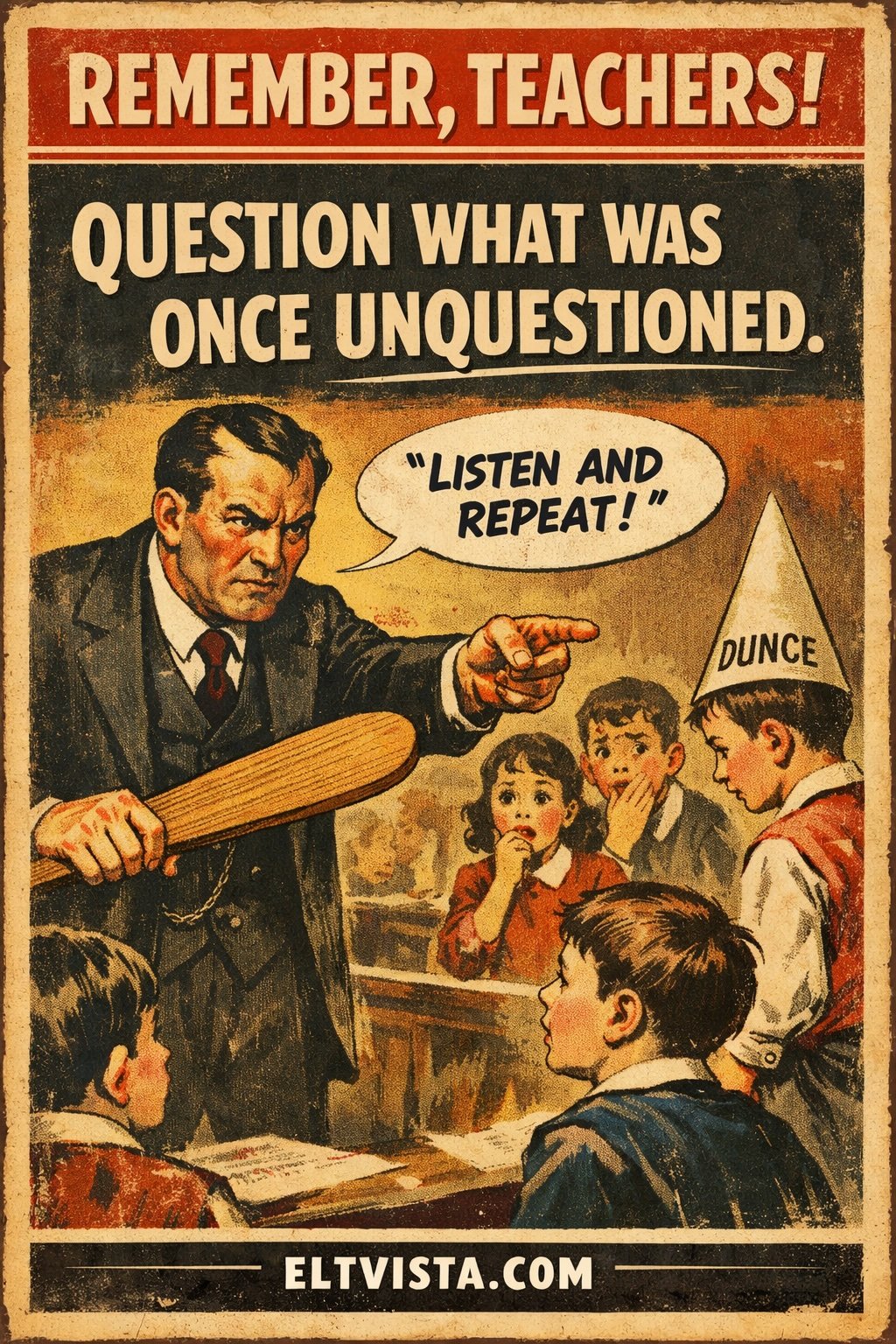

Corporal punishment offers a stark example. Paddling, once widely accepted in schools, was justified as discipline, structure, and even care. Today, many educators find the idea troubling, yet the debate has never fully disappeared. The point is not to relitigate the practice itself, but to recognize a pattern: systems can persist long after we stop questioning their origins.

When Educational Theory Changes Faster Than Practice

This realization should feel familiar to language teachers.

For much of the twentieth century, behaviorist psychology shaped language teaching in powerful ways. Audiolingual classrooms emphasized repetition, imitation, and compliance. Students listened, repeated, memorized, and practiced until the desired behaviors appeared. The approach was systematic, efficient, and reassuringly measurable. It also left a deep imprint on the profession. More importantly, it shaped how teachers learned to relate to students: through control, correction, and compliance.

Constructivist perspectives later transformed how we understand learning. Meaning-making, interaction, and learner agency moved to the center of pedagogy. However, professional habits rarely change as quickly as professional theory. Many teachers continue to navigate a tension between inherited methods and contemporary understanding. The theory changed quickly; the relational habits in classrooms did not.

This is where the real danger begins to emerge. Old habits rarely survive because they are effective. More often, they survive because they are familiar.

Complacency disguised as tradition.

Equilibrium mistaken for progress.

One-size-fits-all as professional comfort.

When familiarity becomes justification, questioning begins to feel unnecessary. This is how inherited practices quietly shift from choice to default, and from default to expectation.

The Comfort of Stability—and the Risk of Complacency

Learning itself is not especially complicated. Messy, perhaps—but not complicated. Human beings learn instinctively, continuously, and often joyfully. The real complexity lies in the systems we build around learning. Over time, these systems can become rigid, procedural, and resistant to change.

The risk is not failure—it is unconscious continuation.

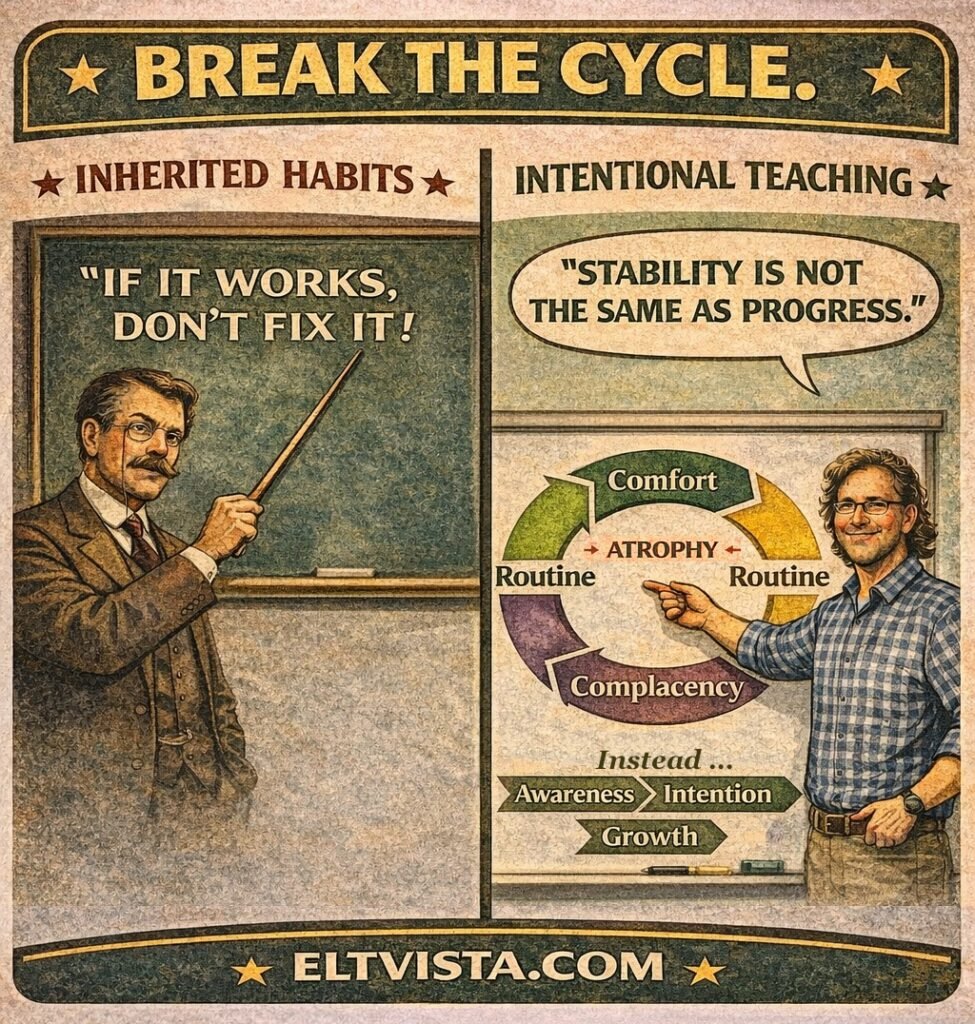

The familiar phrase “If it works, don’t fix it” carries a certain wisdom. Stability matters. Experience matters. Yet professional growth cannot stop at maintenance. In language teaching, we often talk about i+1 for learners: the idea that development happens just beyond the current level of comfort. The same principle applies to teachers.

Without intentional movement forward, we risk becoming proficient in complacency. We become rooted in pedagogical atrophy, investing our energy in maintaining equilibrium rather than pursuing growth. The classroom may appear stable, yet stability alone is not the same as progress.

Moving forward does not require dramatic reinvention. It begins with conscious awareness. Teachers do not need to reject the past. However, we do need to examine what we have inherited and decide what still deserves a place in our classrooms.

What About the Teacher?

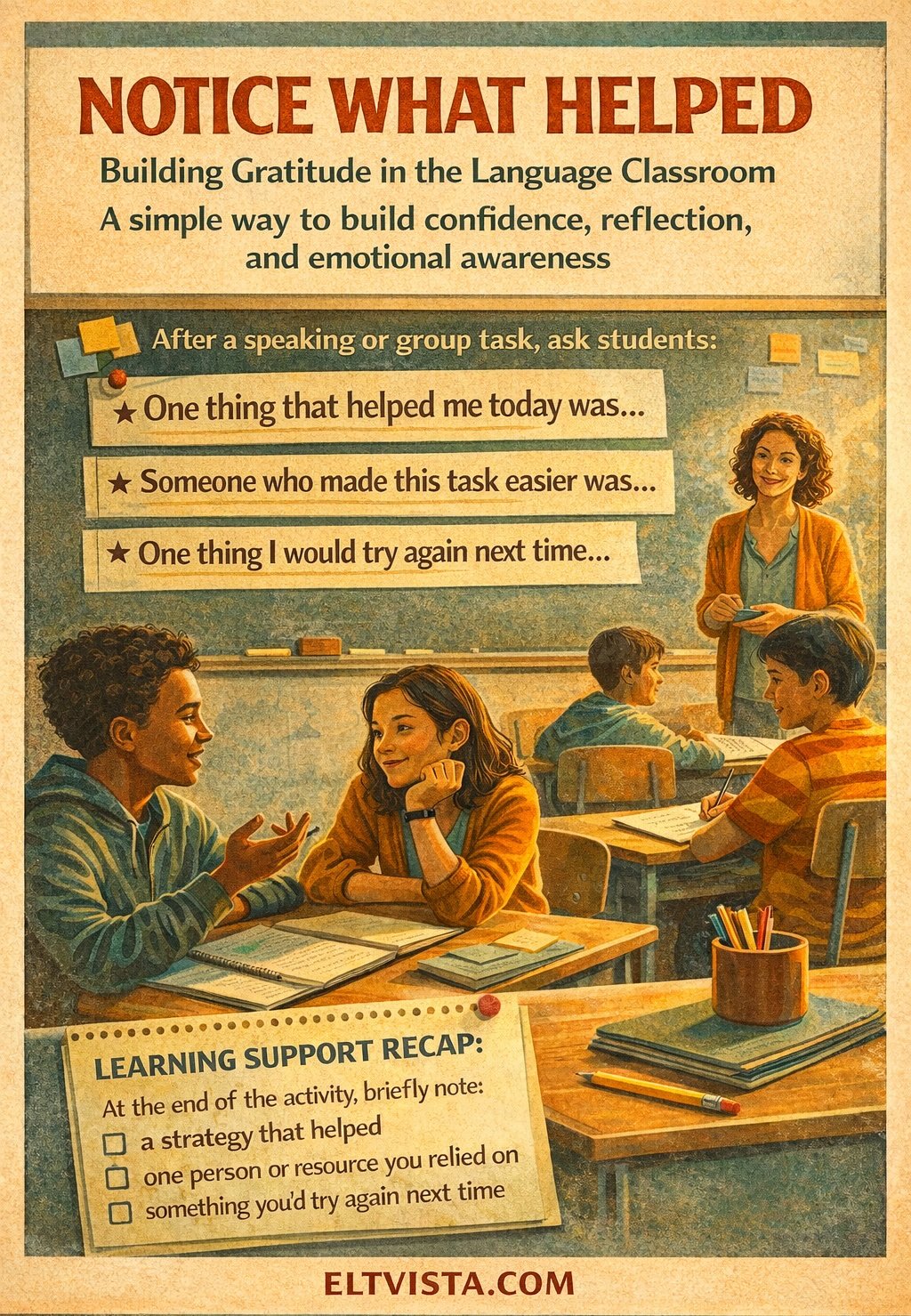

Consider one way you show up for the human beings in front of you. Not a new activity. Not a new technique. A conscious shift in how you relate to your students.

- Perhaps it is choosing patience instead of urgency.

- Perhaps it is choosing curiosity instead of assumption.

- Perhaps it is choosing trust instead of control.

- Perhaps it is recognizing individual differences and learning preferences because you have taken the time to understand what matters to a particular student.

- Perhaps it is following a moment of genuine interest to build connection and discussion, rather than watching the clock and moving on.

Make one change deliberately. Not because novelty is appealing and not because professional growth demands constant experimentation, but because teaching is a human relationship before it is a practice. Purpose and intention—not habit or convention—are what give our choices meaning.

The real question is not what new technique to try next. The question is how intentionally we choose the kind of teacher—and the kind of human presence—we bring into the room.

Inherited systems are not the problem. Unexamined systems are. Teaching moves forward when awareness turns into intention and intention turns into action.

While you are contemplating your personal and profesional development, please consider our self-paced 120-hour online certificate course to your list of teaching qualifications:

For more information, click here for the ELT Vista Certificate in Humanistic TESOL Teaching. Enrollment is now open with a special Holiday Launch promotion!

Also, for more articles like this one, please consider our publication, What About The Teacher?—a humanistic guide to self-actualization for TESOL teachers seeking personal and professional development. The book is available online in both digital and paperback formats at: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0FPBWNXTZ