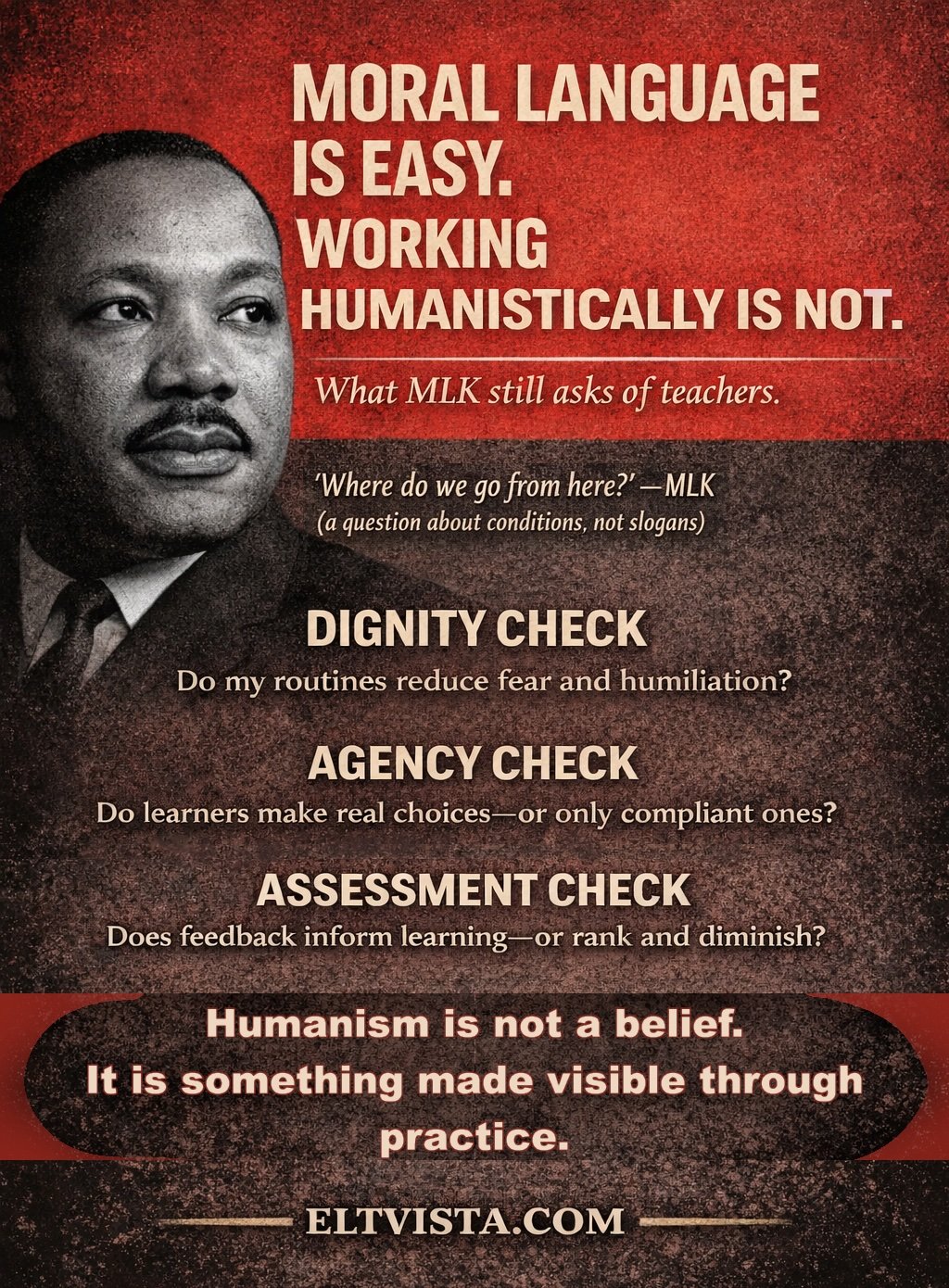

Every year we quote Martin Luther King Jr.

Every year we praise his moral clarity, his courage, his vision of justice and dignity.

At the same time, teachers are told to “be humanistic,” “be learner-centered,” and “support the whole learner” while working under conditions that quietly make dignity harder, not easier, to sustain.

That contradiction is not accidental—and King would have recognized it immediately.

King’s work did not emerge from abstract moral concern. It emerged from material realities faced by African Americans: segregated schools, suppressed wages, restricted housing, blocked civic participation. When he spoke of justice, he spoke about conditions—who carried risk, who absorbed instability, and who was expected to wait patiently while inequality remained intact.

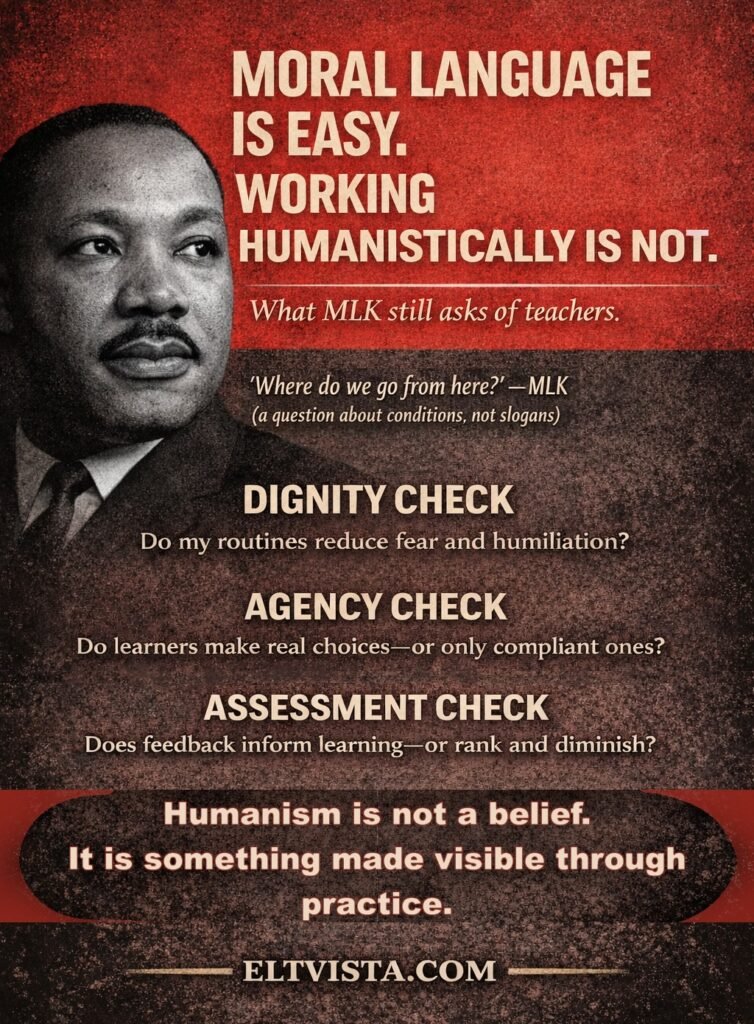

He was clear on one point: moral language without material change is not progress. It is delay.

For teachers, that insight lands close to home.

When Humanism Becomes a Performance

We live in a time saturated with ethical language. Humanism, inclusion, empowerment, and care appear everywhere—in policy documents, professional development sessions, conference keynotes, and social media posts. The language is polished. The values sound right.

The problem is not the language. The problem is what remains unchanged beneath it.

King repeatedly warned against substituting language for change. In speeches such as Where Do We Go from Here?, he cautioned that justice delayed, softened, or abstracted becomes another form of injustice.

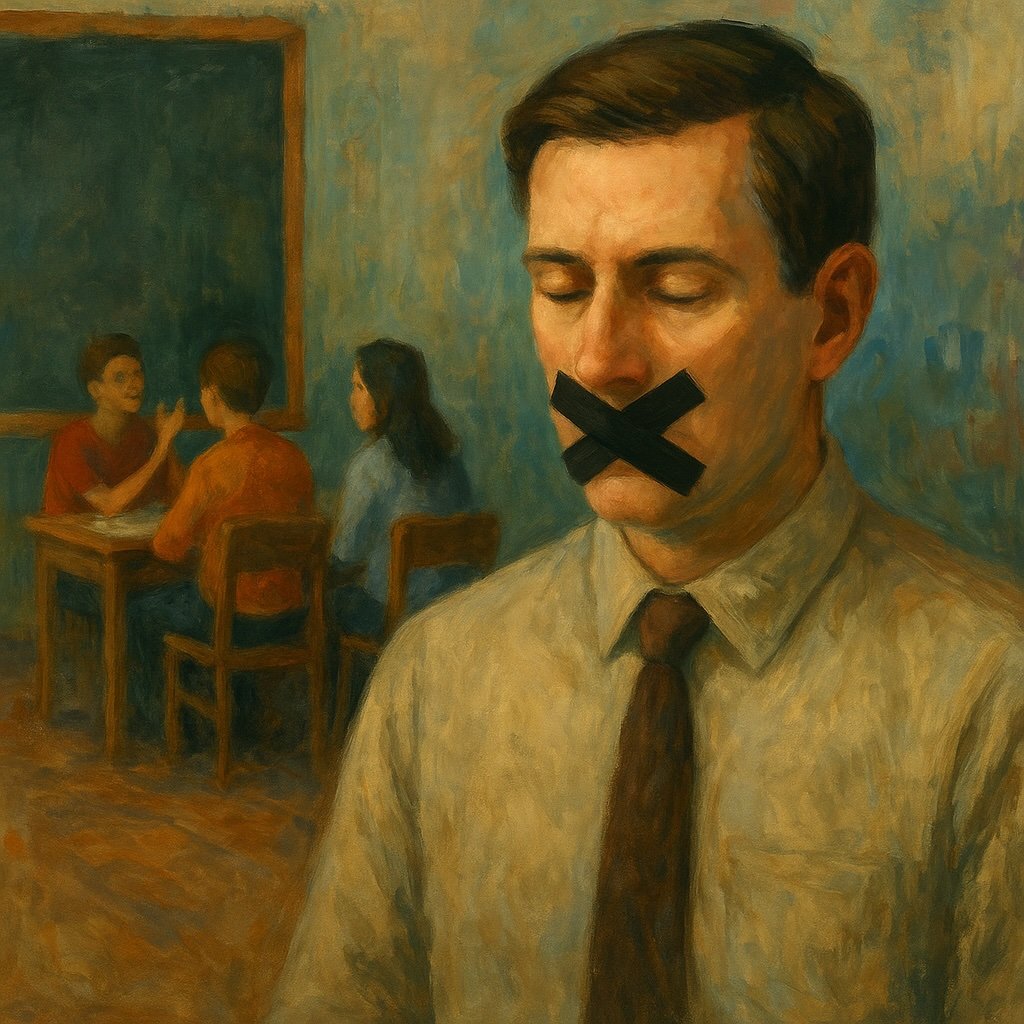

Teachers are asked to enact learner-centered pedagogy in overcrowded classrooms. They are expected to individualize instruction while following rigid pacing guides. They are told to prioritize well-being while navigating surveillance-driven assessment systems and increasing job insecurity.

The words suggest care.

The structures demand compliance.

This is where humanism stops being a value and starts becoming a performance.

The Classroom Has No Moral Distance

At the global level, concern for humanity is often expressed at scale. Problems are discussed in aggregates, projections, and long-term horizons. Responsibility disperses. Consequences feel abstract.

The classroom does not work that way.

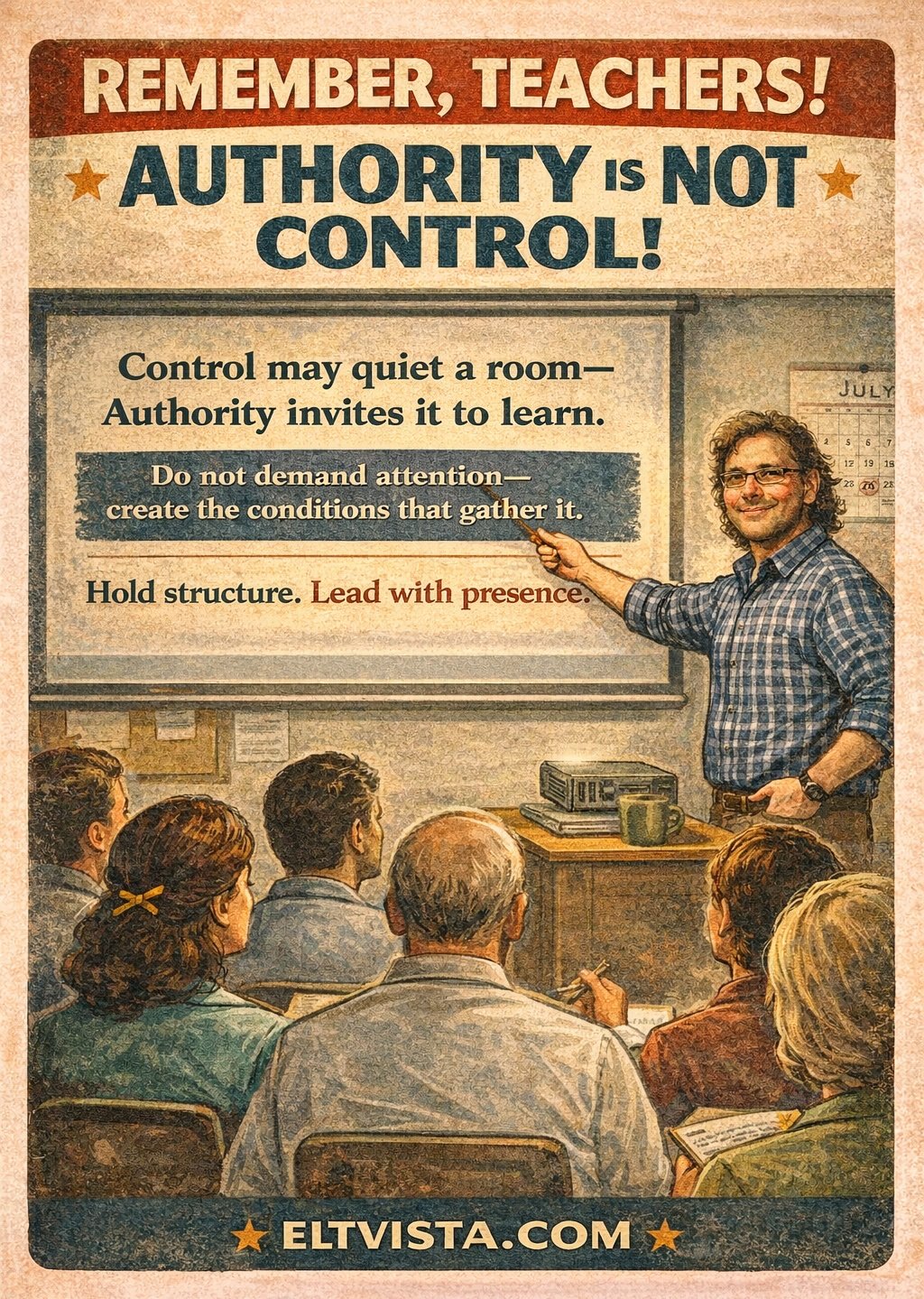

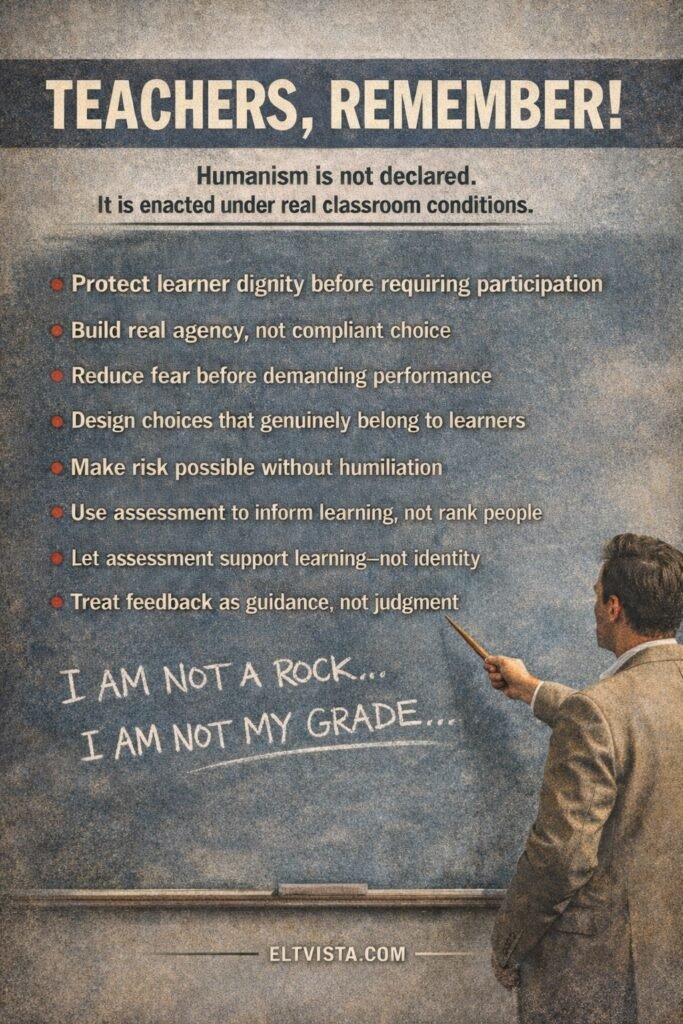

Communicative Language Teaching and learner-centered approaches are built on immediacy. Meaning is negotiated in real time. Power is visible. Decisions about correction, grouping, feedback, silence, and assessment land directly on real people. There is no buffer.

In classrooms, humanism cannot hide behind language. It shows up—or it doesn’t.

Teachers know this. They feel it in the daily friction between what they are told to value and what they are actually able to do.

King’s moral standard was never sentimental. He judged systems by outcomes, not intentions. If a policy sounded just but left people poorer, excluded, or silenced, it failed the test. If moral language improved reputations but not conditions, it was not moral at all.

Why MLK Still Matters Here

King did not ask people to sound humane. He asked them to change conditions. He spoke plainly about exploitation, inequality, and the moral danger of comfort built on injustice. He was deeply suspicious of consensus that left power untouched.

That suspicion matters now.

Education continues to celebrate humanistic ideals while shifting the burden of making them real onto individual teachers. When systems remain unchanged, humanism survives only because teachers absorb the damage—emotionally, professionally, and often financially.

That is not sustainable. It is also not neutral.

What About the Teacher?

What about the teacher who is asked to be endlessly patient inside structures that show little patience in return? What about the teacher who smooths institutional contradictions for learners while carrying the strain privately?

Reflective practice, in this context, is not self-care rhetoric. It is ethical positioning. It is how teachers decide what they will comply with, what they will resist, and where they will draw lines that protect dignity—both their students’ and their own.

Some questions are worth sitting with:

- Where am I being asked to compensate for conditions I did not create?

- Which practices in my classroom genuinely protect learner dignity—and which merely appear to?

- Where does my professionalism end and quiet harm begin?

- What does extending dignity to myself actually require?

A Final Return to the Classroom

Martin Luther King Jr. understood that injustice often survives not through cruelty, but through politeness, delay, and moral language that never quite touches conditions. That insight does not belong only to history.

For teachers, the classroom remains one of the few places where humanism cannot be abstract. It is tested daily, under pressure, in decisions that carry immediate consequences. If humanism is to mean anything beyond ceremony, it has to live there—where teachers work, where learners risk, and where dignity is either practiced or quietly withheld.

This perspective underpins the work we publish at ELT Vista and the design of our Humanistic TESOL Certificate, both of which are dedicated to supporting teachers who want humanism to live in practice rather than rhetoric.

While you are contemplating your personal and profesional development, please consider our self-paced 120-hour online certificate course to your list of teaching qualifications:

For more information, click here for the ELT Vista Certificate in Humanistic TESOL Teaching. Enrollment is now open with a specialHoliday Launch promotion!