Emotions Are Not Extra in Language Learning

Most language classrooms are very good at helping students notice what went wrong. Much less time is spent helping them notice what helped. That imbalance matters. Over time, it shapes how learners experience risk, error, feedback—and ultimately, the language itself.

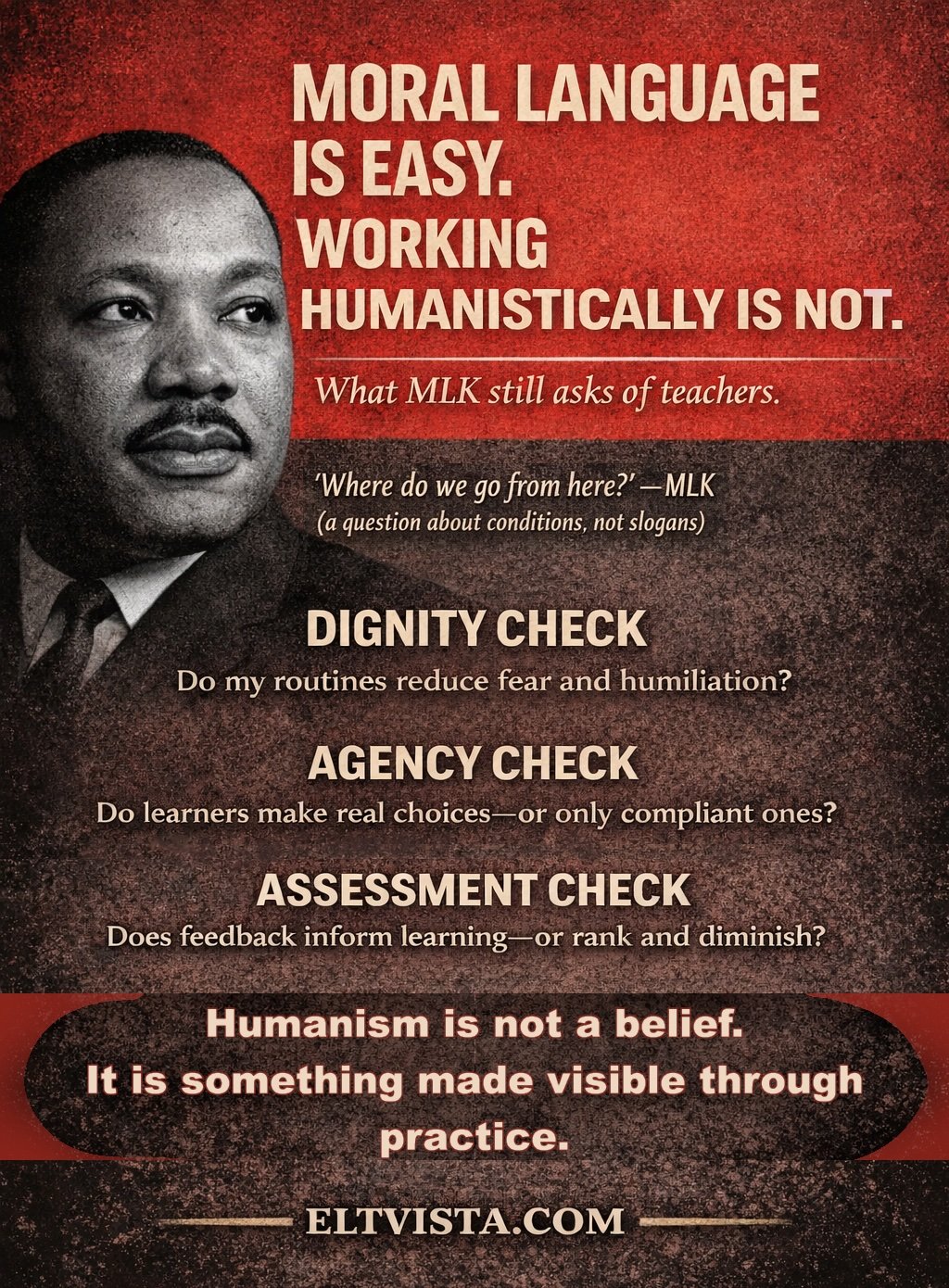

This is where gratitude enters the picture, though not in the way it is often understood. In the language classroom, gratitude is not about politeness or forced positivity. It is about attention—the ability to notice what supported learning while it was happening, rather than only what fell short afterward. In a humanistic TESOL context, gratitude is better understood as an attentional practice: a way of noticing value, effort, and relational contribution in real time.

In language learning, emotions are not background noise. They are part of the medium we teach through. How learners feel about speaking up, making mistakes, or working with others often determines how—and whether—language develops at all. Confidence tightens or loosens. Anxiety narrows attention or becomes manageable. Motivation either grows or quietly slips away. What learners are guided to notice in these moments—failure or support, deficit or contribution—shapes their emotional relationship with the language itself.

Emotional Intelligence (EQ) and Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) operate precisely in these moments. EQ is not a separate “soft skill,” and SEL is not a program to bolt onto a syllabus. They show up in ordinary classroom interactions: how students respond to correction, how they manage uncertainty, how they collaborate, and how they recover when communication breaks down.

Seen this way, gratitude is not an add-on. It is an attentional skill embedded in emotional intelligence itself. A learner who can name what helped them—

a clear instruction,

a supportive partner,

their own persistence—

is also learning to regulate emotion, reflect on process, and stay engaged through difficulty.

When learners are guided to notice these elements, they are not being sentimental. They are practicing emotional awareness and reflection at the same time as language. That shift alone can change how willing they are to take risks, tolerate ambiguity, and remain present in the learning process.

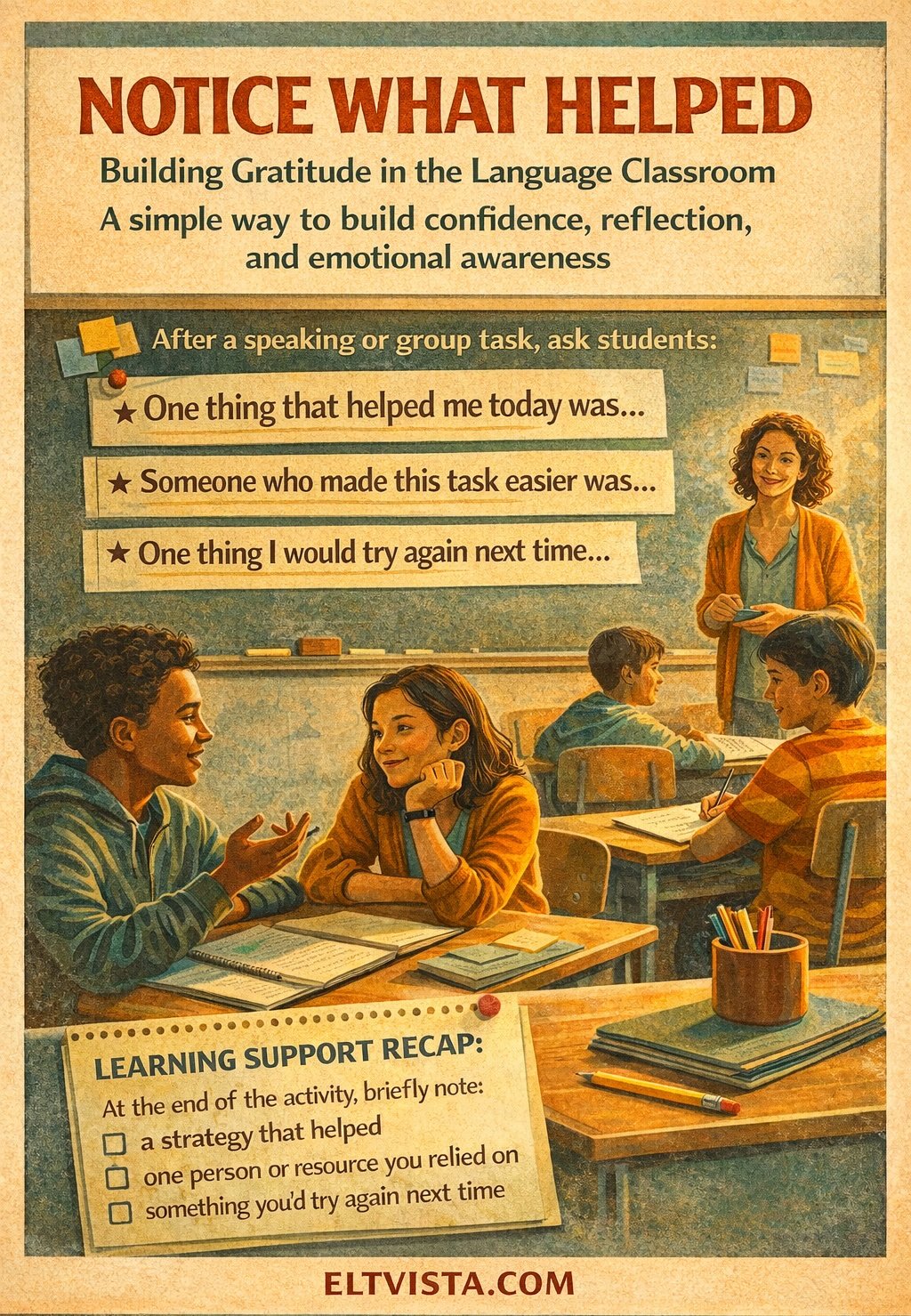

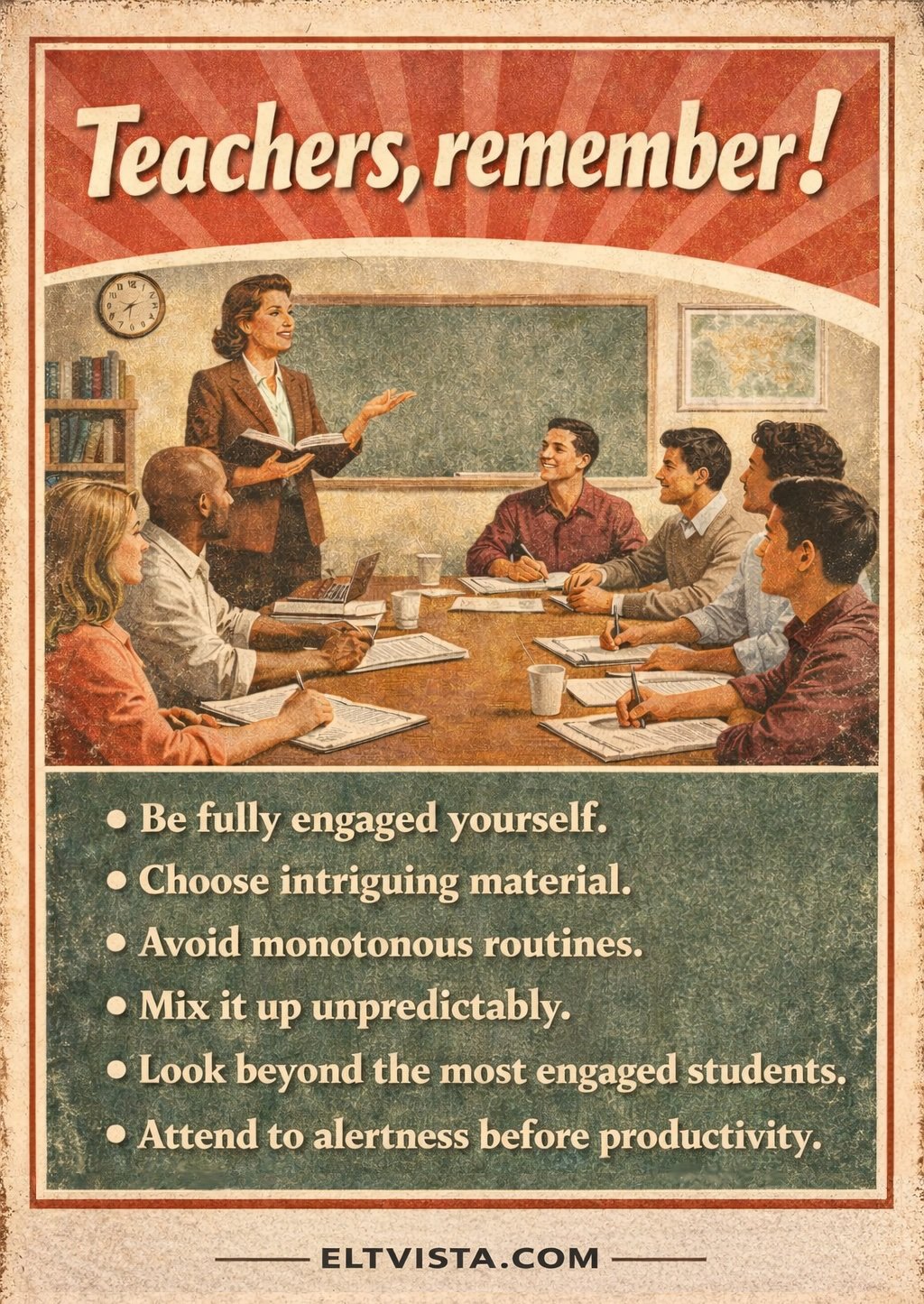

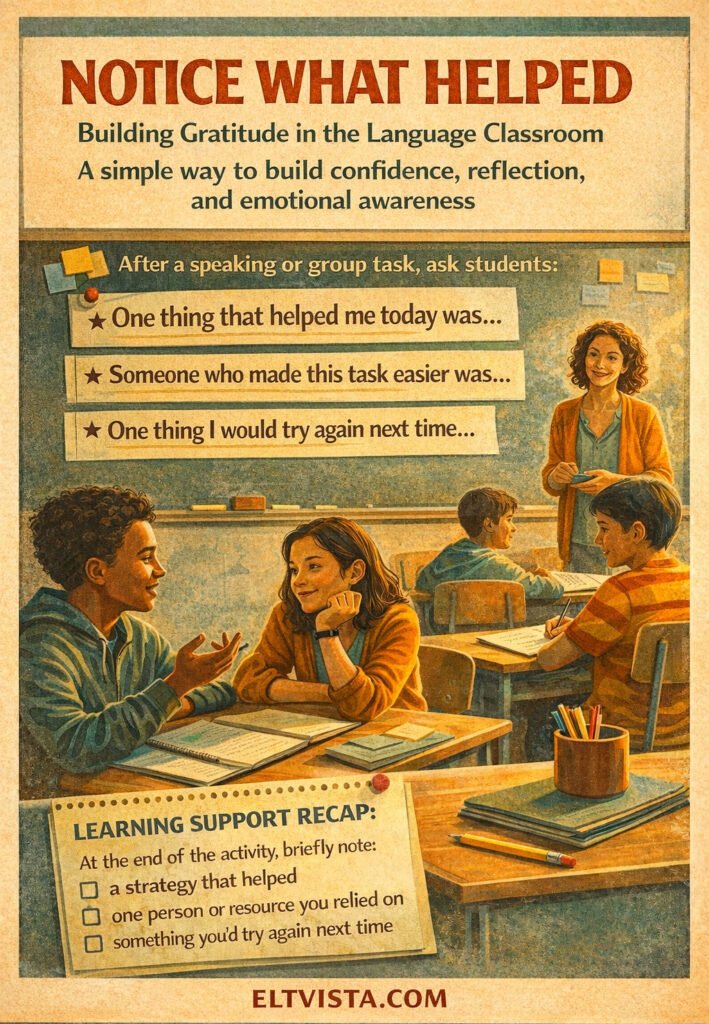

Simple Tasks That Do Real Work

Small routines can go a long way. Short prompts such as “One thing that helped me today was…” or “Someone who made this task easier was…” build emotional vocabulary while reinforcing agency and collaboration.

Another practical task is a “learning support recap.” At the end of an activity, students briefly note:

- one strategy that helped them

- one person or resource they relied on

- one thing they would try again next time

This keeps gratitude grounded in process rather than praise. Learners begin to understand not only what they learned, but how learning happened—and that awareness supports both confidence and autonomy.

Gratitude and Language Anxiety

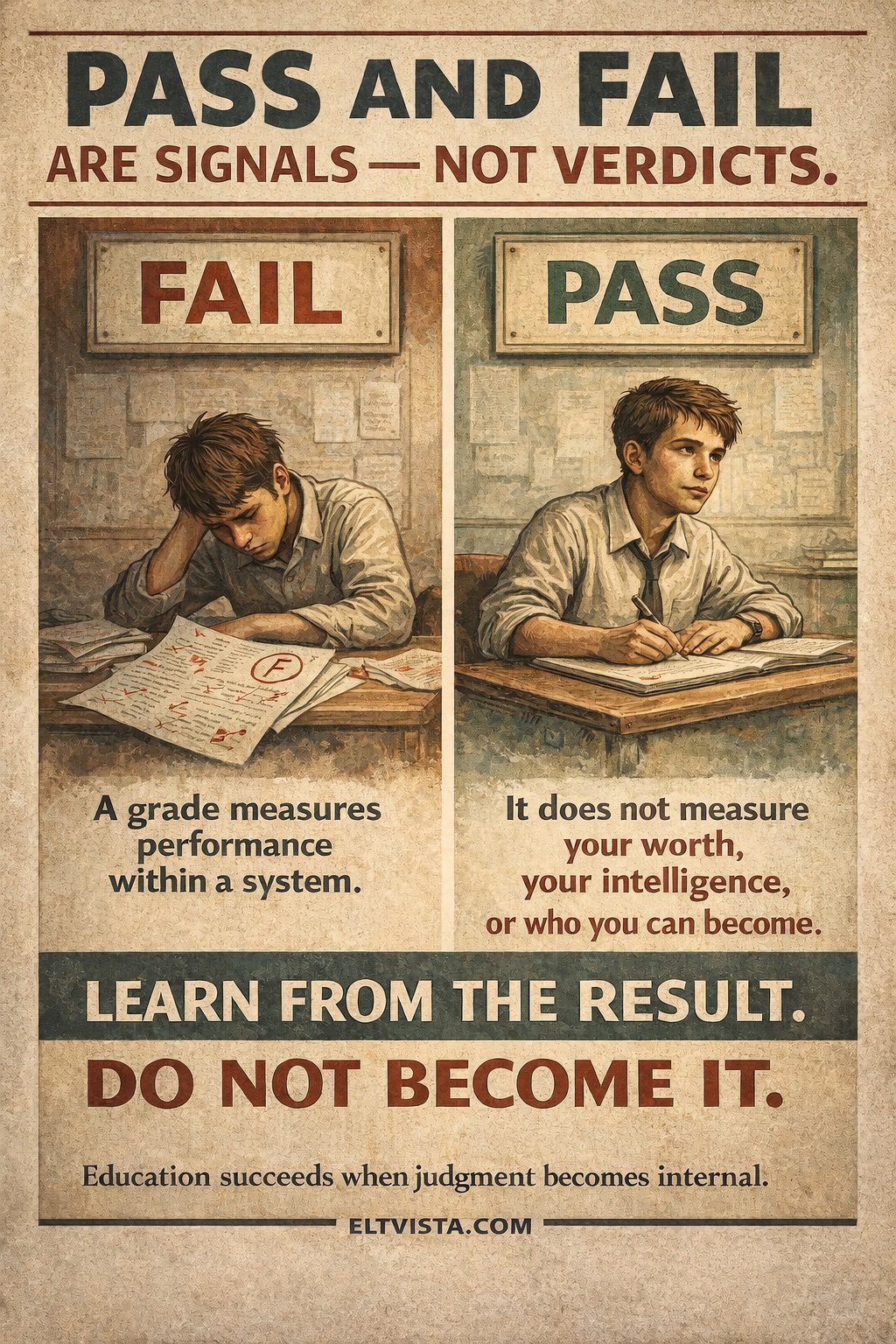

Gratitude also plays a role in managing language anxiety. It does not remove discomfort, but it reframes it. Learners begin to see challenge alongside support, effort alongside progress. That shift alone can make risk-taking feel more possible.

For example, after a speaking task, instead of asking only “What was difficult?”, a teacher might also ask, “What helped you get through it?” A student who struggled to express an idea may notice that a partner waited patiently, that a key phrase was written on the board, or that they kept speaking despite hesitation. Naming these supports does not erase anxiety, but it places it in context.

Over time, students develop a more balanced emotional narrative around learning. Mistakes are still uncomfortable, but they are no longer the whole story. Learners begin to associate speaking not only with fear of error, but with strategies, support, and personal resilience—conditions under which communication becomes possible.

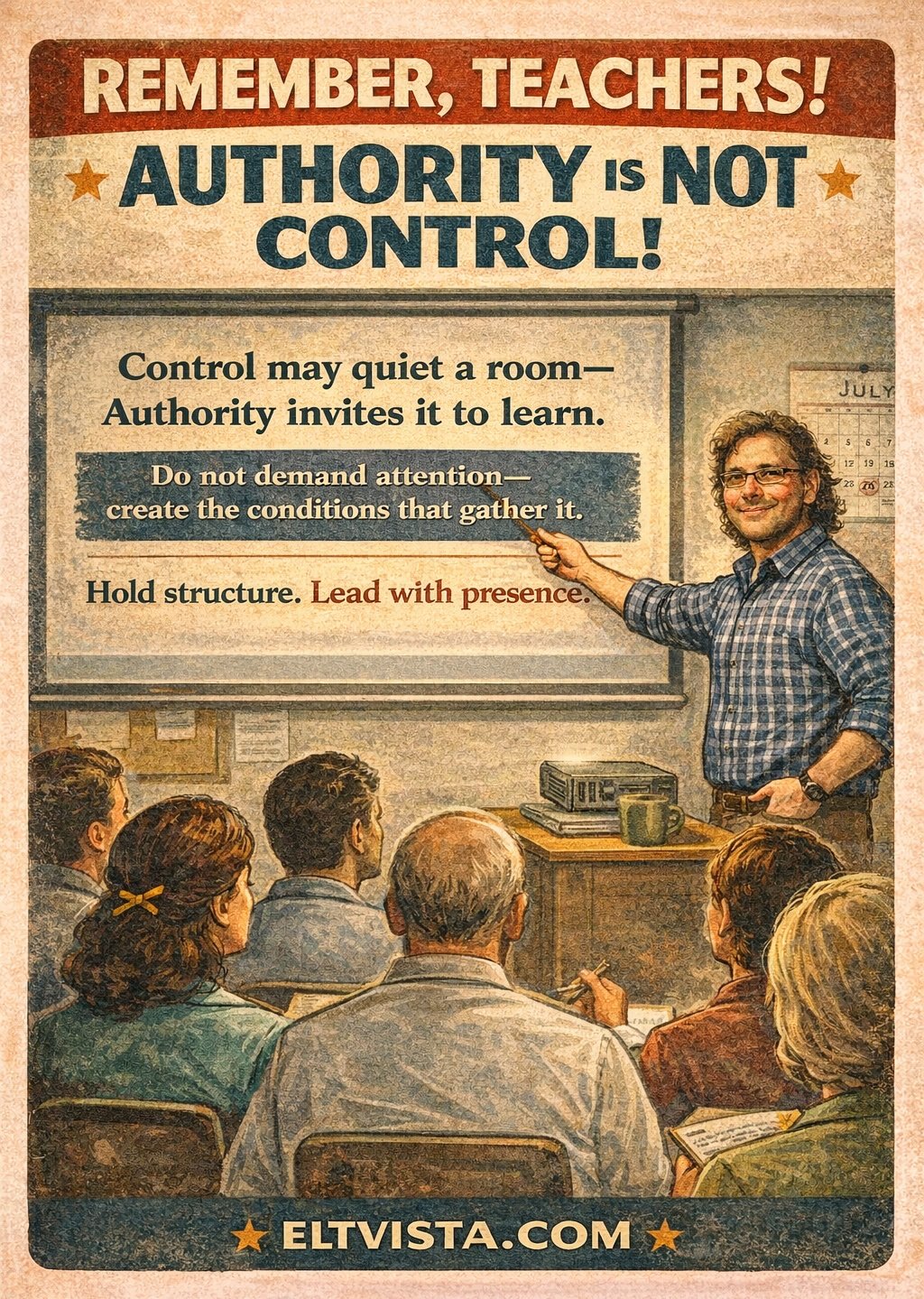

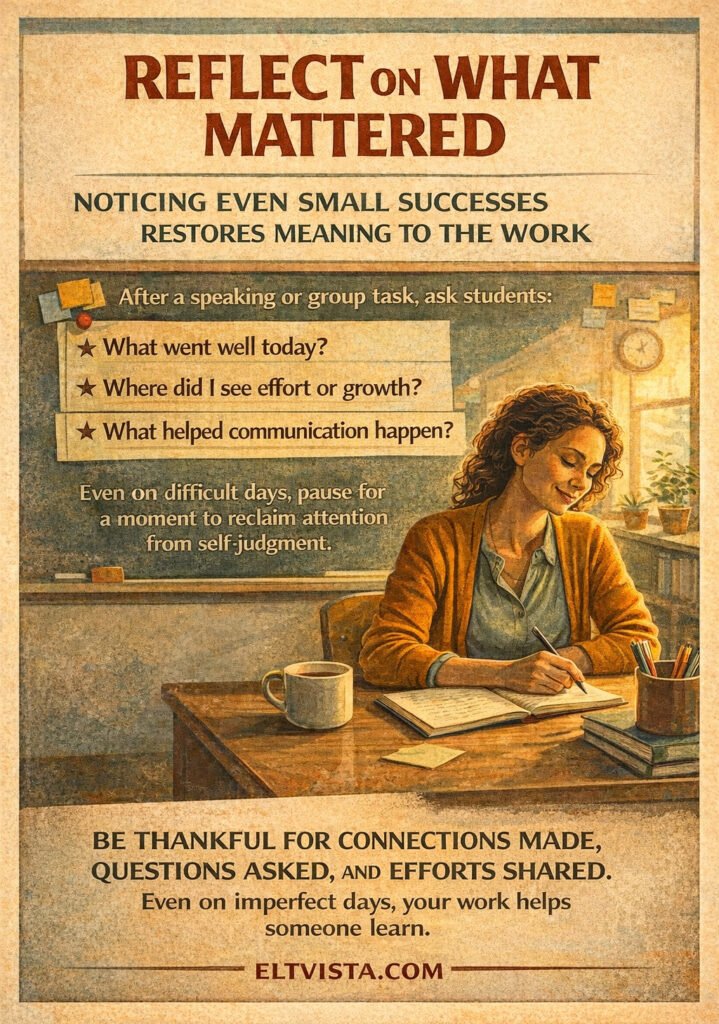

What About the Teacher?

Teachers live inside the same emotional climate they create. Practicing gratitude as a teacher is not about ignoring pressure or lowering standards. It is about reclaiming attention from constant self-judgment.

Noticing a moment of connection, a small breakthrough, or genuine effort restores meaning to the work—especially on imperfect days.

One practical habit is a brief end-of-day reflection, no more than a few lines: What went right today? Where did I see effort, curiosity, or growth—even if the lesson itself felt messy? Over time, this shifts focus from performance to process.

Another useful practice is a post-lesson pause. Before moving on to planning or correction, teachers can ask themselves: What did students respond to? Where did energy rise? What helped communication happen? These questions ground reflection in observation rather than evaluation.

When teachers model calm recognition rather than performance-driven praise, they model emotional intelligence in action. They show students how to hold frustration and appreciation at the same time. That modeling does more for classroom culture than any checklist ever could.

Keeping the Work Human

Seen this way, gratitude is not an add-on. It is a grounding practice—for learners and teachers alike. It supports Emotional Intelligence, strengthens SEL, and helps keep language teaching human, relational, and sustainable.

In a profession built on communication, that may be one of the most practical skills we can cultivate.

While you are contemplating your personal and profesional development, please consider our self-paced 120-hour online certificate course to your list of teaching qualifications:

For more information, click here for the ELT Vista Certificate in Humanistic TESOL Teaching. Enrollment is now open with a specialHoliday Launch promotion!