Rethinking Quality from the Inside Out

The phrase quality management rarely excites classroom teachers. For many, it conjures images of accreditation visits, institutional audits, observation rubrics, and administrative paperwork. It sounds managerial, corporate, and distant from the daily realities of teaching. Most teachers assume that quality management is something handled by directors of studies, academic managers, or school owners rather than by the person standing in front of the class.

For many teachers, the phrase feels imported from another world—one of audits, checklists, and accreditation visits rather than lesson planning and learner relationships. This distance matters, because it shapes how teachers respond to the idea before the conversation even begins.

However, in truth, this assumption deserves a closer look. Because long before institutions began measuring quality, teachers were already trying to improve it.

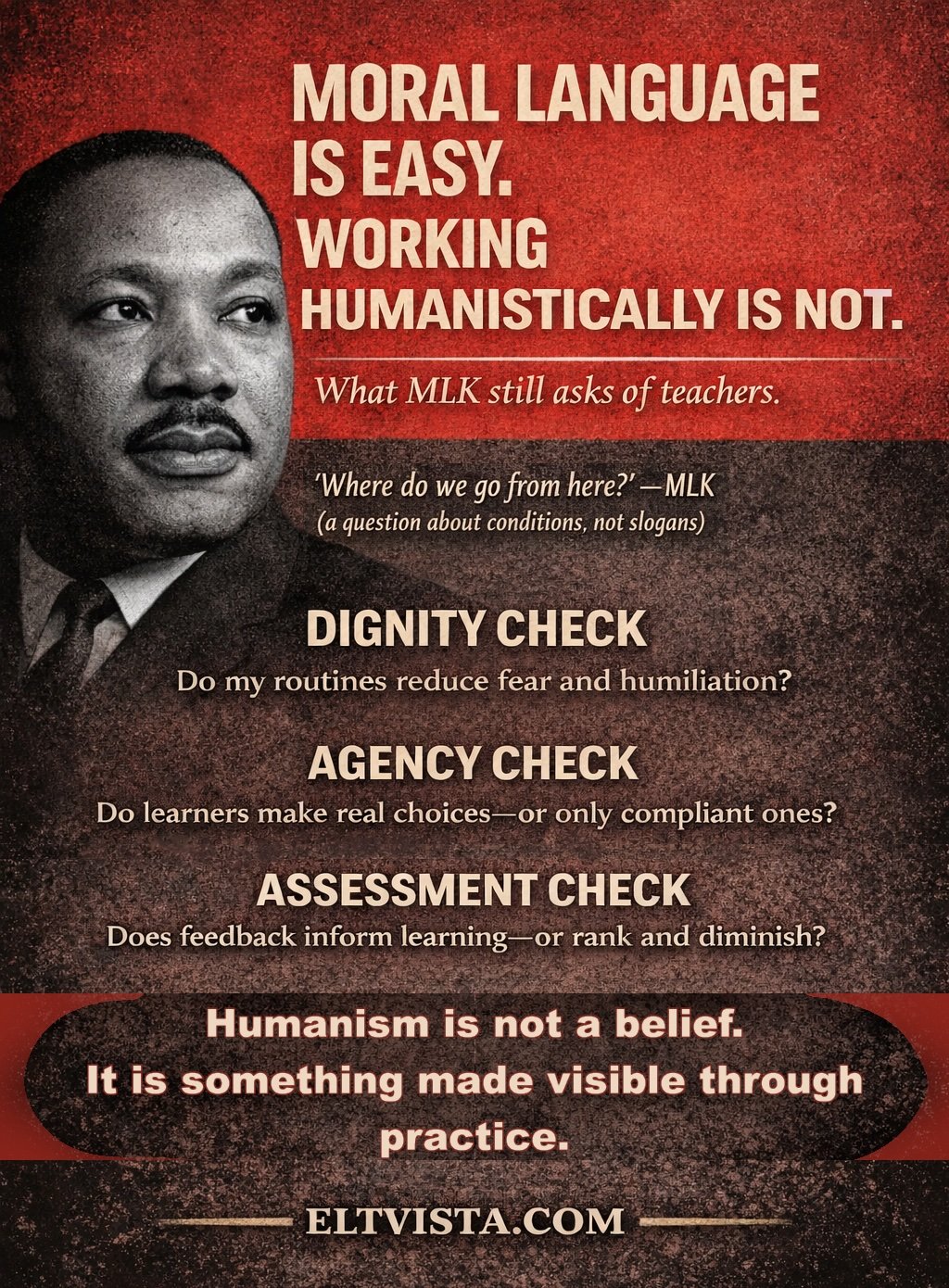

This article begins a short series exploring the relationship between quality management and teaching practice. The aim is not to turn teachers into managers or to promote bureaucratic thinking. Instead, the goal is to explore whether the idea of quality has always existed inside teaching under different names—and what it might mean when viewed through a humanistic lens.

Future articles in the series will explore how institutions interpret quality, where industrial models enter education, and whether humanistic teaching can coexist with accreditation frameworks. This first article starts somewhere much closer to home: the classroom.

What Do We Mean by “Quality”?

Before continuing, the term itself requires clarification. To explore this tension, it helps to step away from institutional language and look more closely at what teachers already do every day in their classrooms.

In industry, quality management refers to a set of practices designed to ensure that products and services are consistent, reliable, and continuously improving. The goal is not only to maintain standards but also to reduce recurring problems and improve outcomes over time.

Although the terminology sounds corporate, the underlying ideas are surprisingly simple:

- noticing what works

- noticing what does not work

- making small adjustments

- observing the results

- repeating the process

In organizational contexts, this cycle is often called continuous improvement—the ongoing effort to make processes more effective and more reliable.

Teachers already recognize this cycle. They simply call it experience.

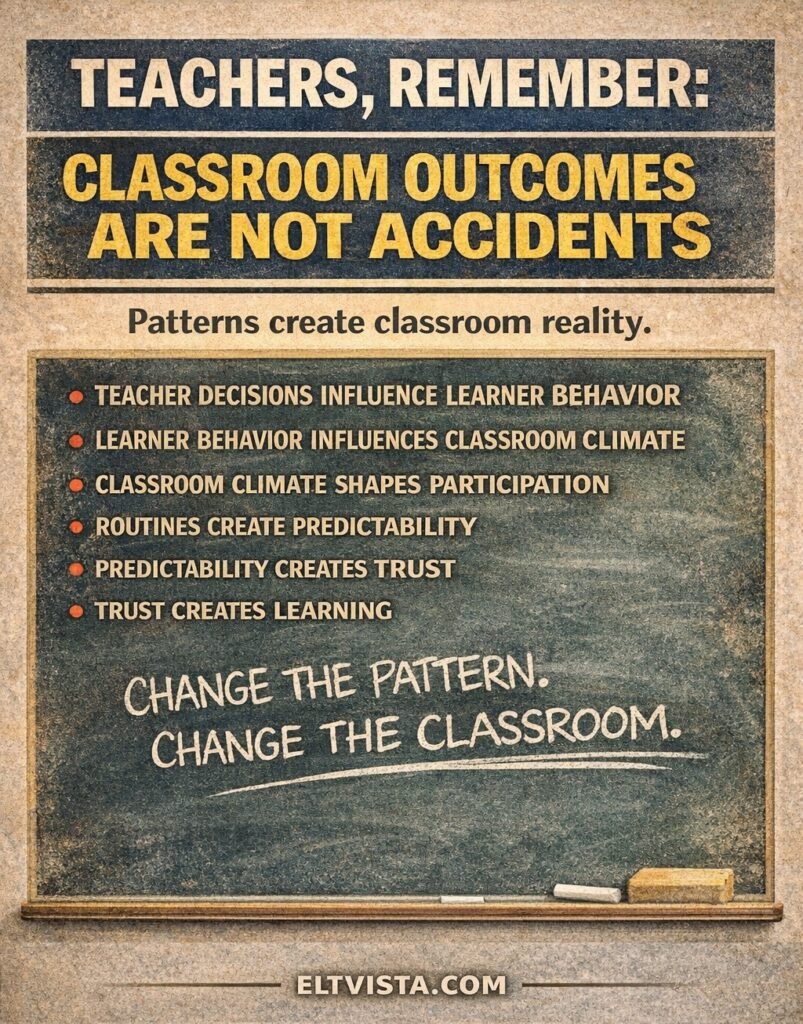

The Classroom as a Living System

Every classroom operates as a small, live system. A system can be defined as a set of interacting elements that influence one another. In a classroom, these elements include:

- the teacher

- the learners

- the materials

- the activities

- the physical and emotional environment

- the routines and expectations that develop over time

None of these elements exist in isolation. Each lesson is shaped by how they interact.

Teachers feel this intuitively. Some lessons feel smooth and predictable. Others feel chaotic and rushed. Some groups quickly develop trust and confidence. Others remain hesitant and distant for weeks.

These differences rarely happen by accident. They emerge from patterns. Recognizing patterns is the first step in understanding quality from a teacher’s perspective. At this point, the idea of quality begins to shift from something external and imposed to something observable and lived within daily practice.

The Difference Between Good Days and Reliable Practice

Teachers often describe lessons emotionally:

“That class went well.”

“That activity flopped.”

“Today felt chaotic.”

“This group is easy to teach.”

These reactions are natural precisely because teaching is a deeply human profession, and emotional responses are part of reflective practice. However, emotional reactions do not always reveal the full picture.

A lesson that felt successful once may not work the following week. An activity that fails in one group may succeed in another. Over time, teachers begin to notice recurring friction points:

- instructions that students regularly misunderstand

- transitions that consistently take longer than expected

- activities that repeatedly lose momentum

- tasks that reliably increase engagement

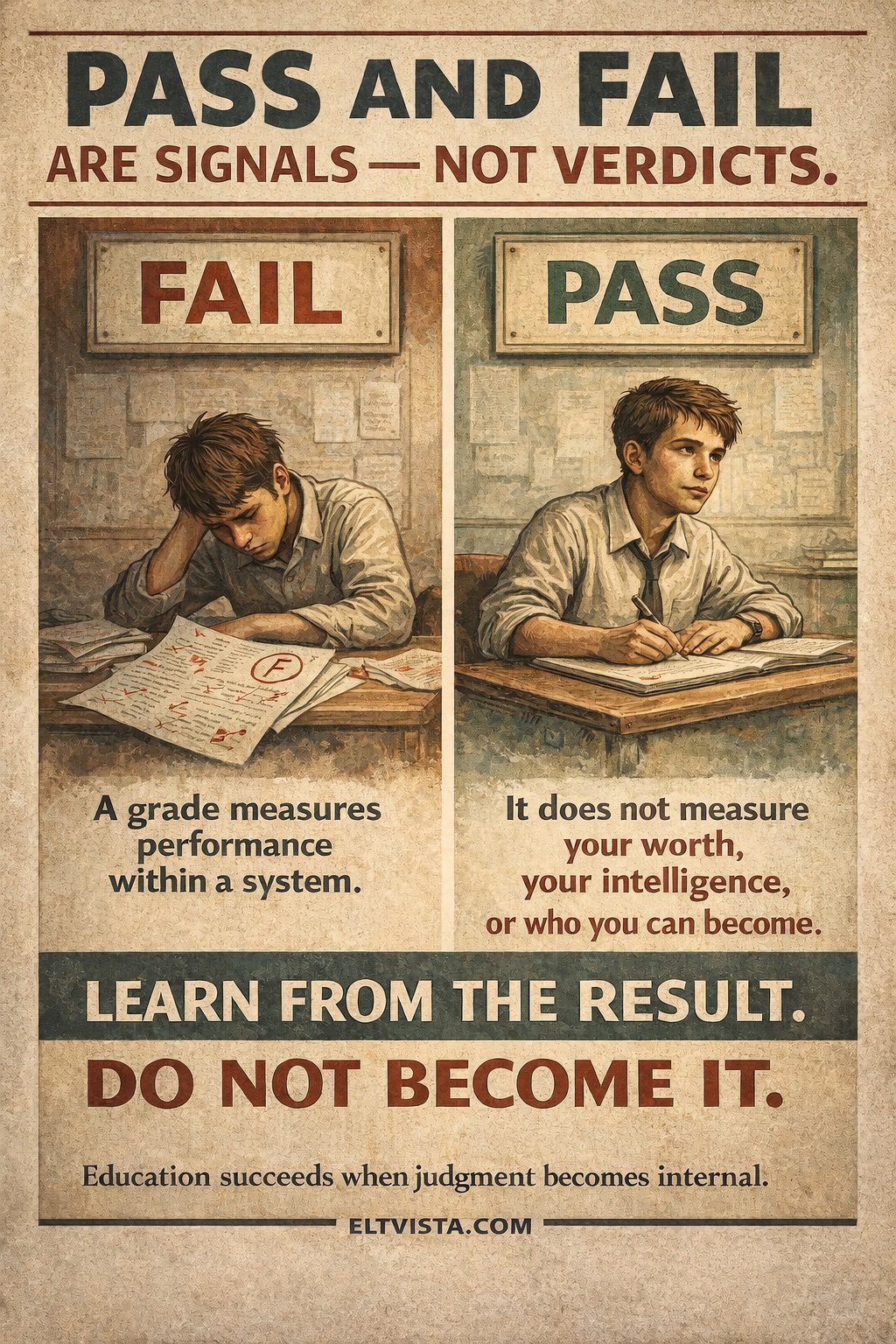

At this point, reflection begins to shift from emotion to pattern recognition. This shift marks the quiet beginning of quality thinking.

Reflection as Continuous Improvement

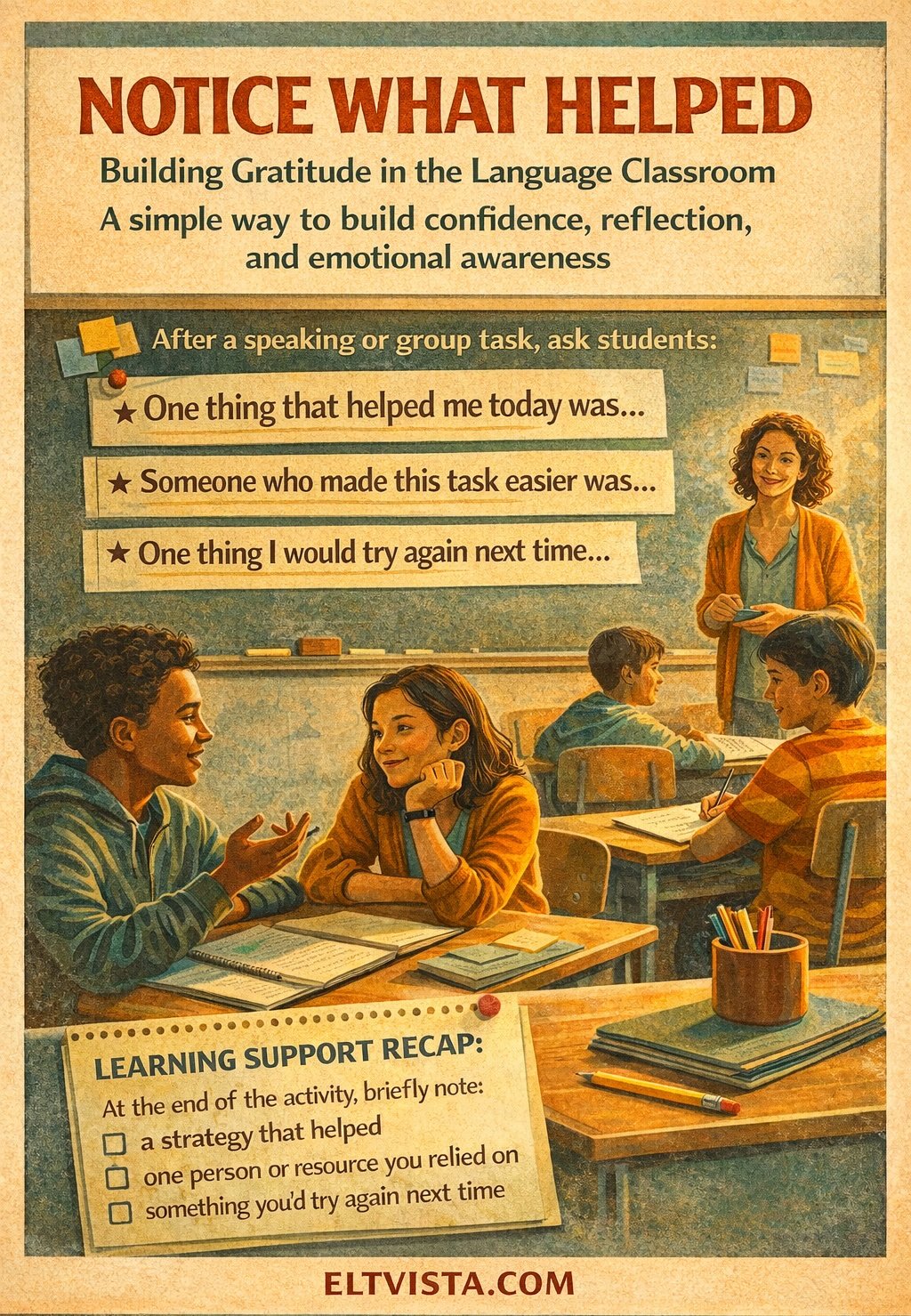

In professional development contexts, teachers are often encouraged to engage in reflective practice.

Reflective practice refers to the ongoing process of examining one’s teaching in order to improve it. This includes noticing classroom dynamics, evaluating lesson outcomes, and adjusting future lessons accordingly.

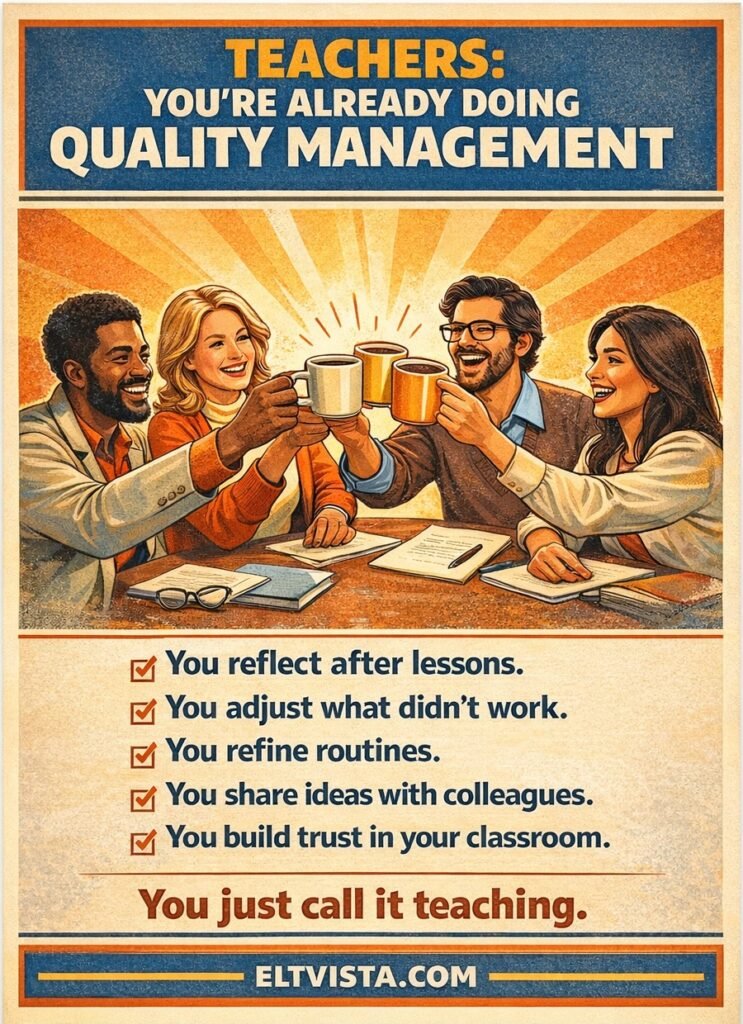

In other fields, this same idea is called continuous improvement. The terminology differs. However, the intention is the same. And, as such, teachers are already engaged in quality management every time they ask:

- How can I give clearer instructions next time?

- How can I make transitions smoother?

- Why do students always struggle with this stage of the lesson?

- What helped this activity succeed today?

These questions are not bureaucratic. They are professional. They are human. They are the foundation of craft. The language may be new. Yet, the practice is not.

Quality Without the Paperwork

At the institutional level, quality is often associated with standardization and compliance. Schools must demonstrate consistency across classrooms and provide evidence of effective teaching practices. The same tends to apply to testing when we speak of validity, reliability, etc.

From a teacher’s perspective, however, quality looks very different. For teachers, quality is often experienced as the reliability of daily practice and the consistency of the learning environment. Through this lens, students experience quality as:

- clarity

- predictability

- fairness

- emotional safety

- a sense of progress

- a sense of belonging

These elements cannot be reduced to a checklist, yet they strongly influence learning outcomes. In other words, the most powerful quality system in any school may be the one already operating inside each classroom.

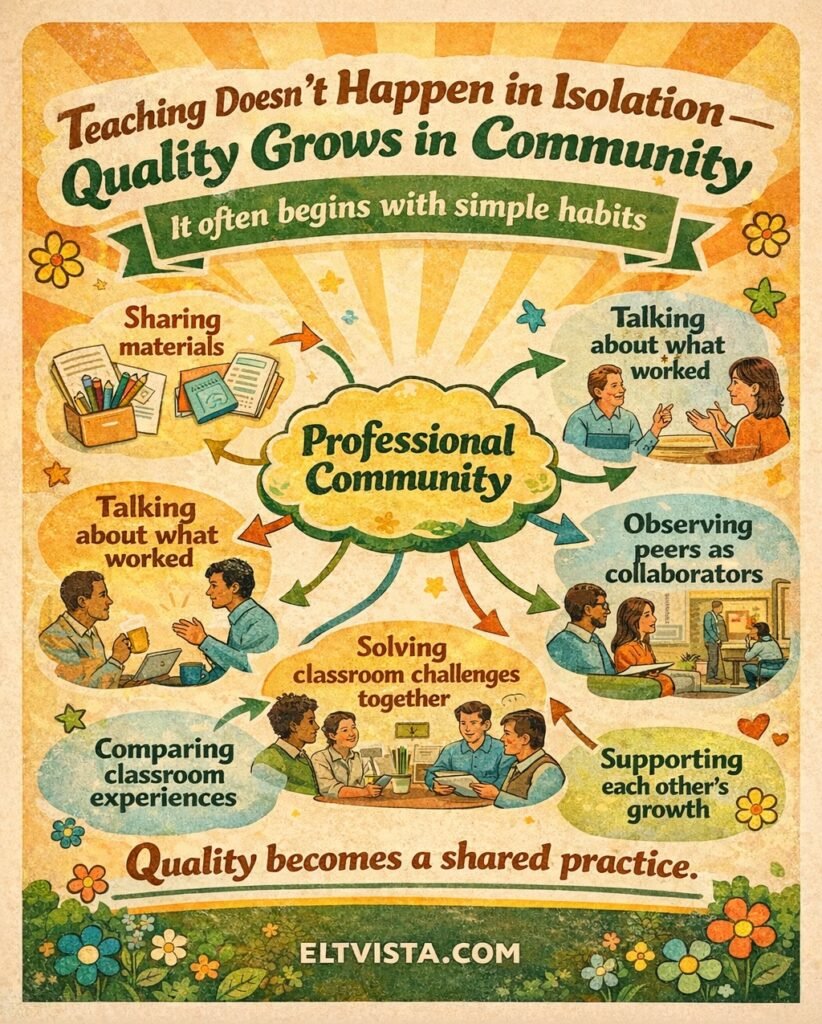

From Classroom Practice to Professional Community

However, classrooms do not exist in isolation. Every teacher works within a wider professional environment shaped by colleagues, shared expectations, and institutional culture.

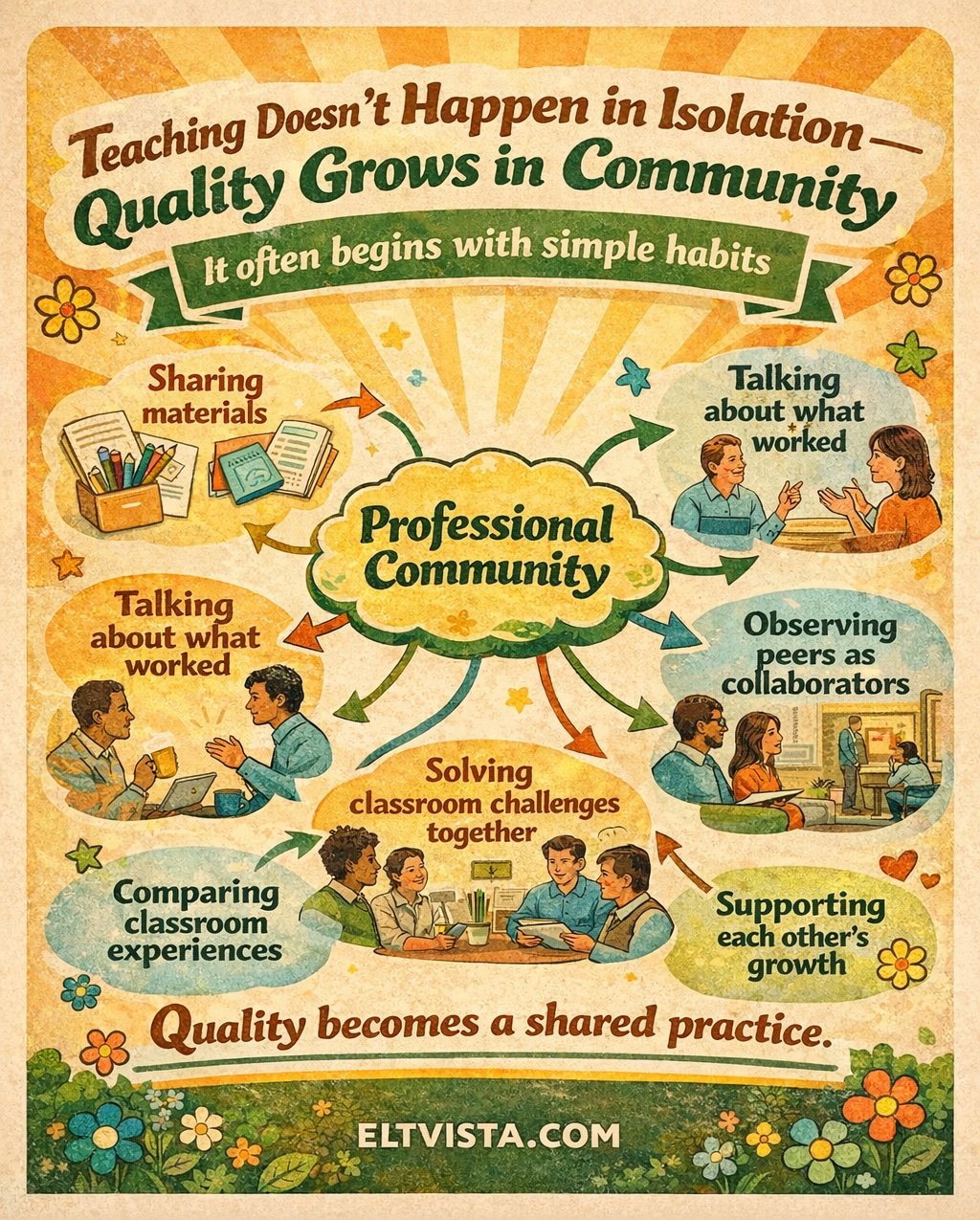

In organizational language, this environment is often described as professional culture. In education, it is more helpfully understood as professional community.

A professional community refers to the network of relationships through which teachers share ideas, compare experiences, solve recurring problems, and support one another’s growth. Informal conversations in staffrooms, shared materials, peer observations, and collaborative planning are all examples of this community in action.

When teachers discuss what worked in a lesson, they are exchanging more than just anecdotes. They are sharing data in human form. When colleagues compare classroom challenges, they are identifying patterns across contexts. When teachers observe one another, they are expanding their understanding of practice beyond the boundaries of a single classroom.

In industry, improvement becomes sustainable when it moves beyond individuals and becomes part of organizational culture. The same principle applies in education.

A single teacher can refine classroom practice. A community of teachers can transform an institution—assuming the institution invites them to the table to do so. Unfortunately, this is not always the case.

This shift does not require formal programs or complex systems. It begins with simple professional habits:

- asking colleagues how they handle recurring classroom challenges

- sharing materials and classroom routines

- observing peers as collaborators rather than evaluators

- normalizing open conversations about what does not work

These actions gradually create a culture in which improvement is shared rather than isolated. Quality, in this sense, becomes a collective practice rather than a private burden.

Looking Ahead

This article has focused on quality from the teacher’s perspective: reflection, pattern recognition, the classroom as a living system, and the role of professional community. The next article in this series will explore how teachers can move from reflection to reliability—how small, intentional changes can reduce classroom friction and create more consistent learning experiences without turning teaching into a mechanical process.

Later articles will move outward to examine how institutions interpret quality, where industrial models enter education, and whether humanistic teaching and formal quality frameworks can genuinely coexist.

For now, one idea is enough to carry forward:

Teachers have always been engaged in quality management.

They have simply been calling it experience.

While you are contemplating your personal and profesional development, please consider our self-paced 120-hour online certificate course to your list of teaching qualifications:

For more information, click here for the ELT Vista Certificate in Humanistic TESOL Teaching. Enrollment is now open with a special Holiday Launch promotion!