Using Climate Change as a Communicative Learning Context

Language does not develop in isolation. It grows through interaction—through the willingness to speak, to listen, to misunderstand and try again. In communicative language teaching, this is not incidental; it is foundational. Yet we often treat classroom discussion as communication. In practice, it becomes rehearsal for winning rather than an opportunity for shared understanding. When learners feel emotionally safe and taken seriously, they are more willing to take linguistic risks, share ideas, and engage meaningfully with language. For this reason, open communication and empathy are not “soft skills.” They are core pedagogy.

This becomes especially clear when classrooms engage with complex, real-world topics—topics that do not have simple answers and that touch on values, fears, and identities. Climate change is one such topic. It is emotionally charged, socially divisive, and often difficult to talk about calmly. Precisely for that reason, it offers a powerful opportunity for communicative language teaching when approached with care.

The goal, however, is not debate as combat. In a communicative classroom, the aim is not to win an argument, but to practice inquiry: asking questions, listening across differences, clarifying meaning, and responding with respect. If greater awareness emerges, that is a shared gain—not a victory over others.

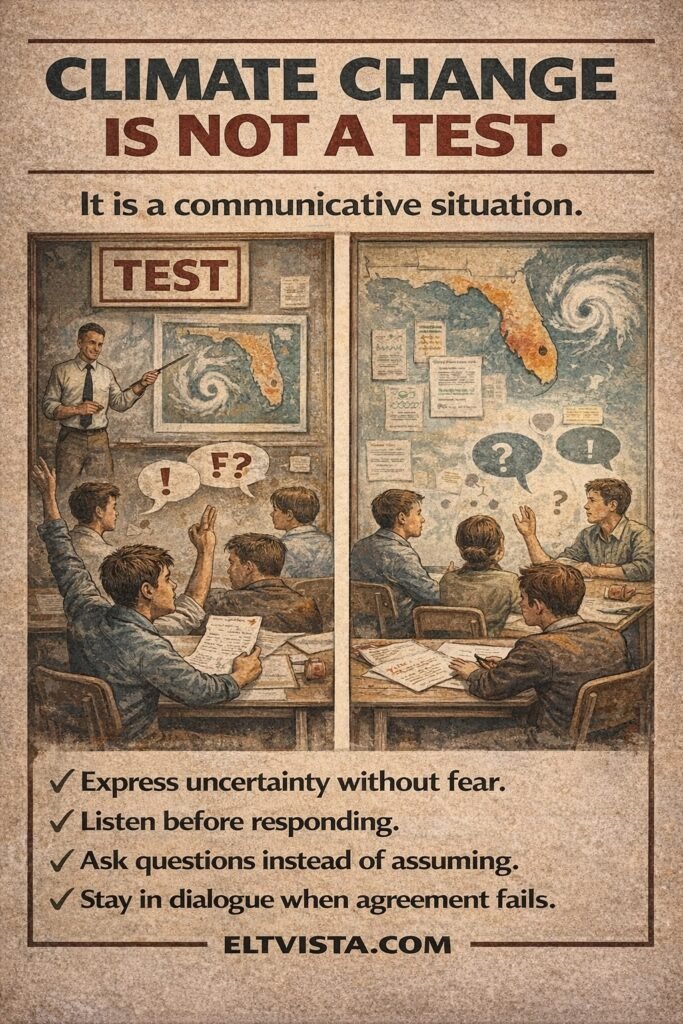

Climate Change as a Communicative Context (Not a Test of Beliefs)

In many classrooms, teachers avoid topics like climate change because they fear conflict or discomfort. Yet avoiding difficult topics does not teach students how to communicate about them—it simply postpones the problem.

From a Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) perspective, climate change is not primarily a scientific lesson or a moral lecture. It is a high-stakes communicative context. Talking about it requires learners to:

- express uncertainty and opinion

- listen to perspectives they may not agree with

- manage emotional responses

- ask clarifying questions rather than making assumptions

These are precisely the skills communicative language teaching seeks to develop.

When handled thoughtfully, climate-related discussions allow learners to practice language as it is actually used in the world: to explore meaning, negotiate viewpoints, and remain in dialogue even when consensus is unlikely.

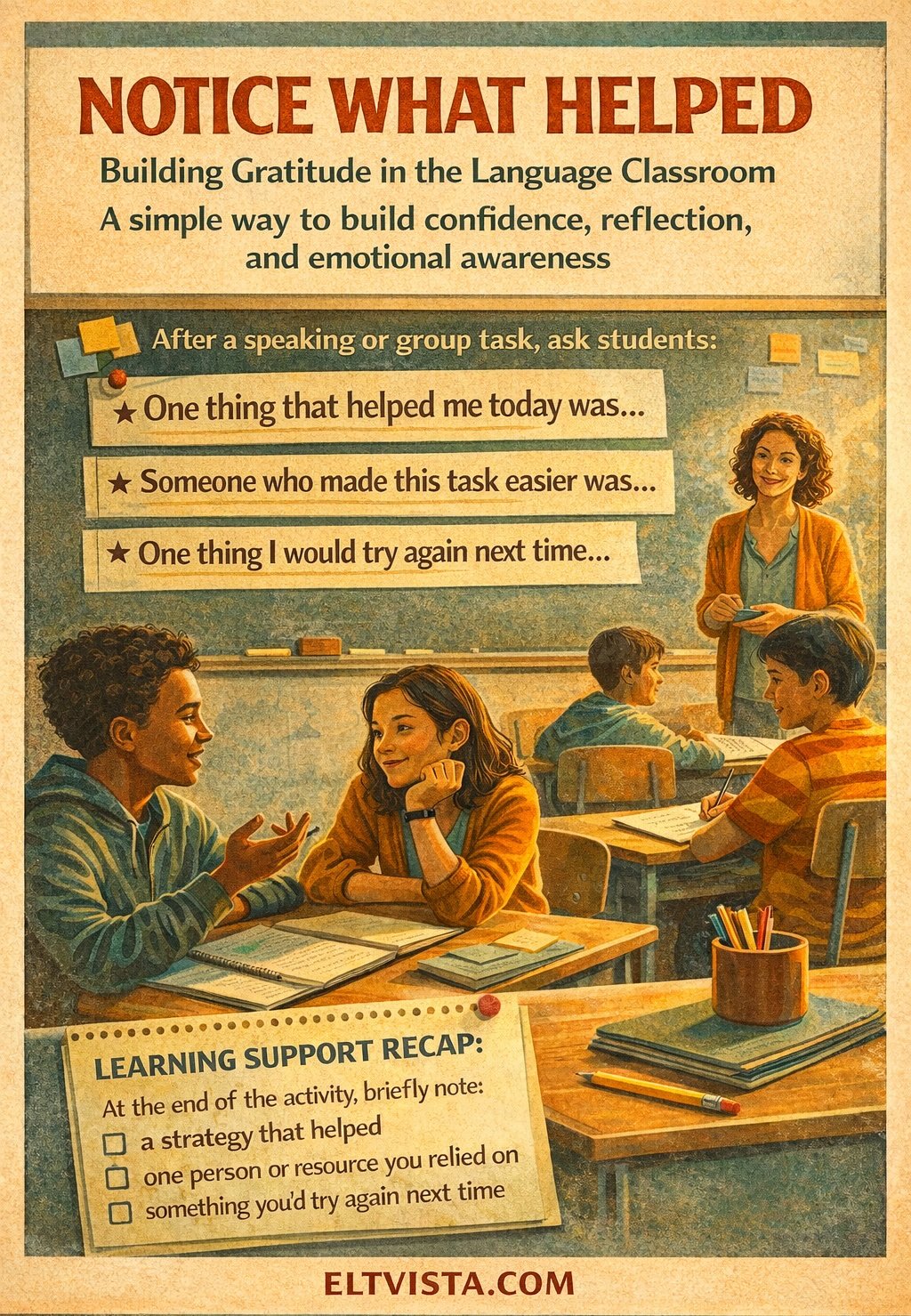

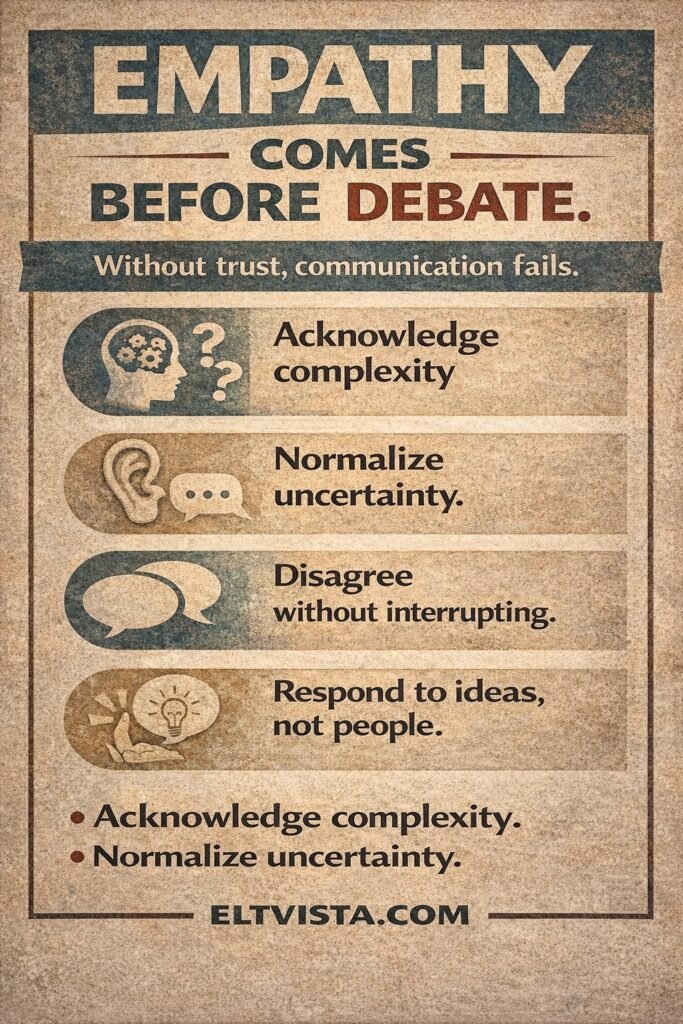

Setting the Conditions: Empathy Before Debate

Before introducing any sensitive topic, the teacher’s role is to establish conditions of trust. Without these, even well-designed communicative tasks will fail.

Some practical steps include:

Modeling openness as a teacher

Acknowledge complexity. Statements such as, “People see this issue very differently, and that’s okay,” or “We’re here to explore ideas, not judge them,” signal safety and intent.

Normalizing uncertainty

Encourage phrases like:

“I’m not sure, but…”

“I’m still thinking about this…”

“From my experience…”

This reduces pressure to perform certainty and invites genuine communication.

Establishing discussion norms

Co-create simple guidelines with learners: listening without interrupting, disagreeing politely, and responding to ideas rather than people. This mirrors real communicative communities and reinforces learner responsibility.

In communicative teaching, trust is not a warm-up—it is the infrastructure.

Designing Climate-Related Communicative Tasks (CLT-Focused)

The following task types keep the emphasis on language use, inquiry, and empathy, rather than persuasion.

1. Opinion Continuum (Speaking & Listening)

Present a statement such as:

“Individual lifestyle changes matter more than government action in addressing climate change.”

Students place themselves on a continuum (agree → unsure → disagree). They then explain why, using language of reasoning and experience.

Key language focus:

- expressing opinion

- qualifying statements

- responding to others

Crucially, students are encouraged to ask follow-up questions, not rebut.

2. Perspective Exchange (Paired Speaking)

Students receive short role cards representing different viewpoints (e.g., a factory worker, a farmer, a student activist, a small business owner). Their task is not to defend the role aggressively, but to explain concerns and priorities.

Follow-up reflection:

- “What was difficult about expressing this perspective?”

- “What did you understand better after listening?”

This supports empathy while remaining communicative rather than performative.

3. Reflective Listening Task

One student shares a personal reaction to climate-related news (interest, concern, skepticism, fatigue). The partner must paraphrase the message before responding.

This reinforces the idea that communication succeeds only when understanding is demonstrated, not assumed.

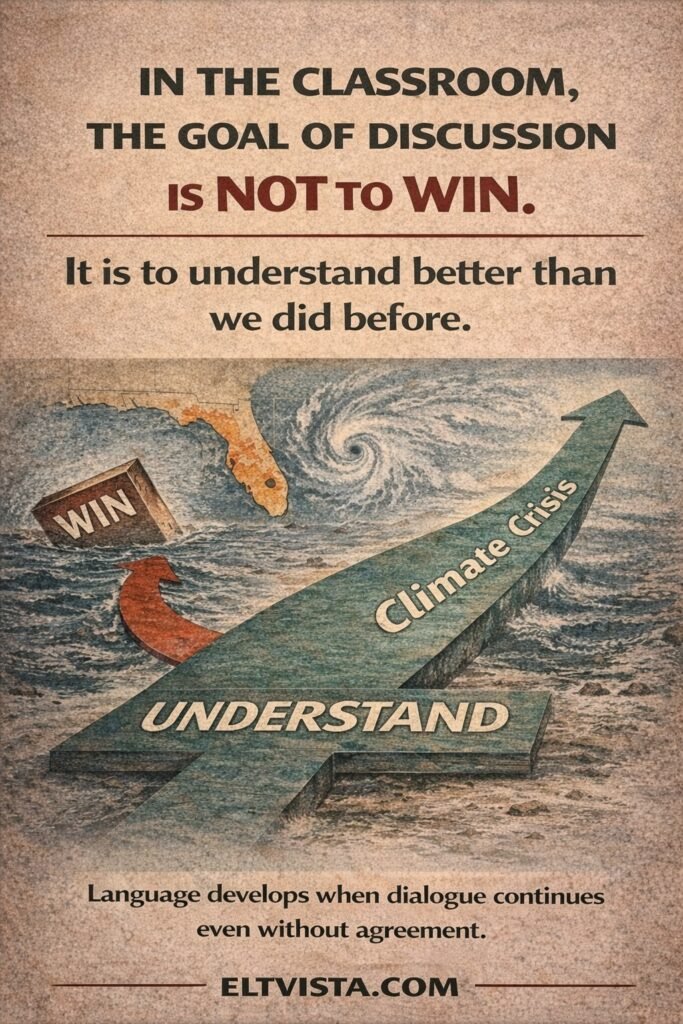

Inquiry Over Winning

One of the most important messages to communicate explicitly to learners is this:

In this classroom, the goal of discussion is not to win.

It is to understand better than we did before.

When climate change is framed this way, debate becomes exploration. Language becomes a tool for inquiry rather than defense. Learners practice staying present in conversations that are uncomfortable, ambiguous, or emotionally charged—an essential real-world skill.

From a communicative standpoint, this is where fluency deepens. Students are no longer rehearsing opinions; they are negotiating meaning in real time.

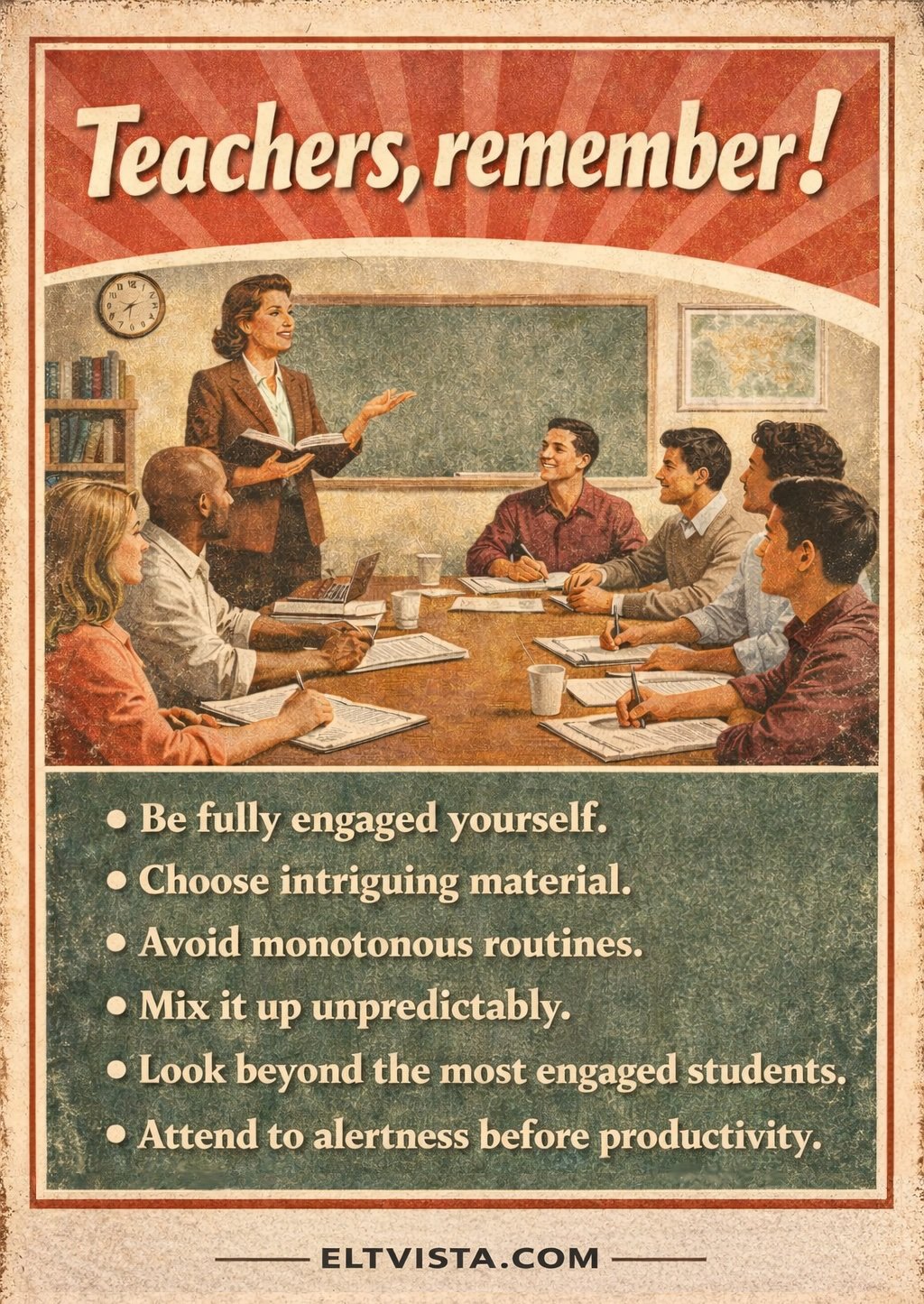

What About the Teacher?

It is easy to support empathy and openness in theory. In practice, teachers may unconsciously steer discussions toward comfort, agreement, or premature closure.

A useful reflective question is this:

Do I allow difficult conversations to unfold, or do I rush to neutralize discomfort?

Climate-related discussions often reveal our own limits—our tolerance for disagreement, silence, or uncertainty. Observing how we respond in these moments is a form of professional growth.

A brief self-check after class might include:

- Did I listen more than I corrected?

- Did I allow multiple perspectives to stand?

- Did I model curiosity rather than control?

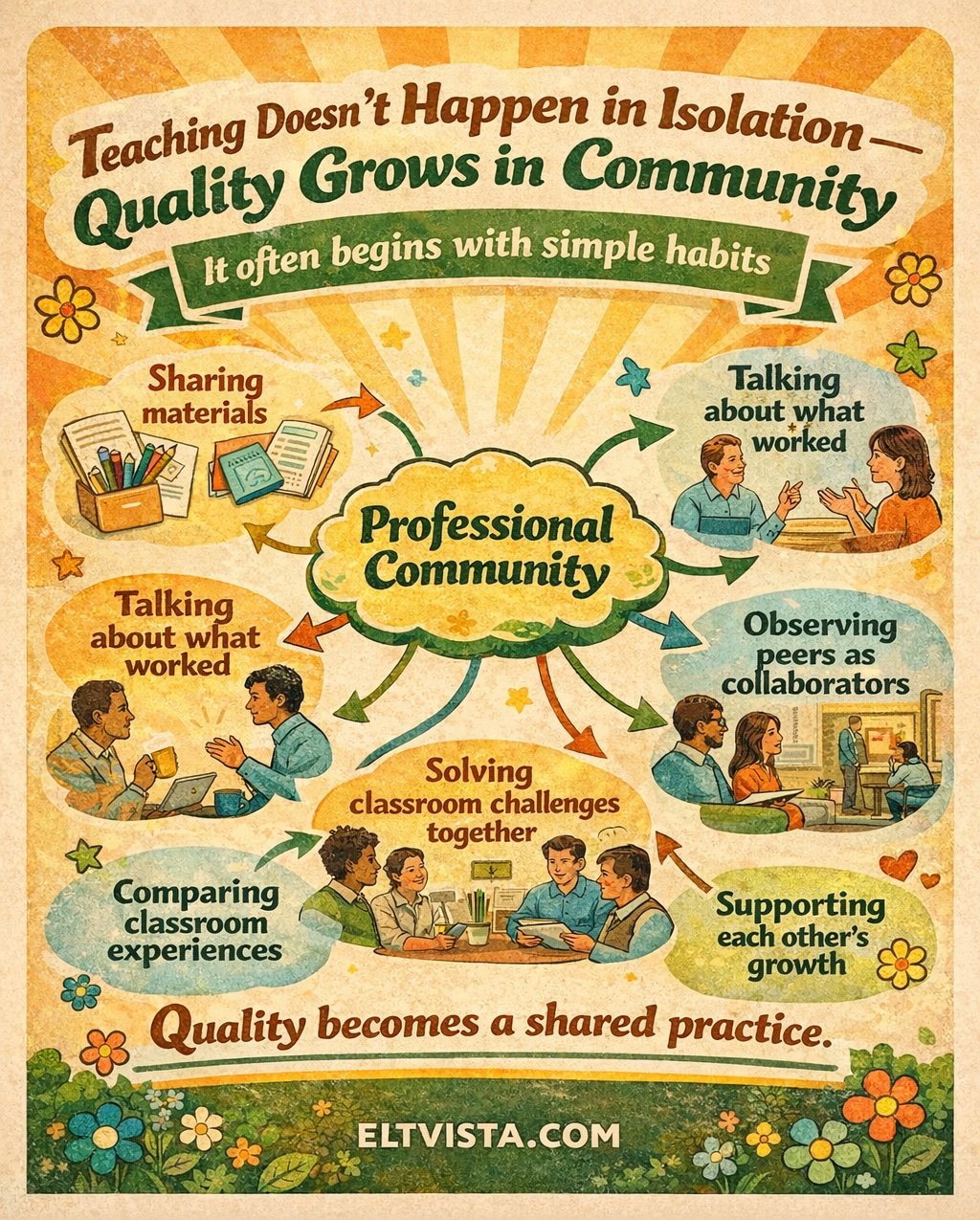

Teacher development, like language development, happens inside and between people. When we treat communicative classrooms as spaces for shared inquiry, we are not only teaching English—we are practicing the very empathy and openness we hope learners will carry beyond it.

If this question feels familiar, it’s one I return to often—here, and throughout my work at ELT Vista.

For more articles like this, please consider our publication, What About The Teacher?—the main text upon which the our online certificate course in humanistic TESOL teaching is based. The book is available online in both digital and paperback formats at: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0FPBWNXTZ

✨ While you are contemplating your personal and profesional development, as well as your New Year’s resolutions, please consider adding our self-paced 120-hour online certificate course to your list: For more information, click here for the ELT Vista Certificate in Humanistic TESOL Teaching. Enrollment Is Open Now with a special! Holiday Launch promotion! ✨