Grades, Judgment, and the Machinery of Worth

Nobody ever tells students the most dangerous thing about grades:

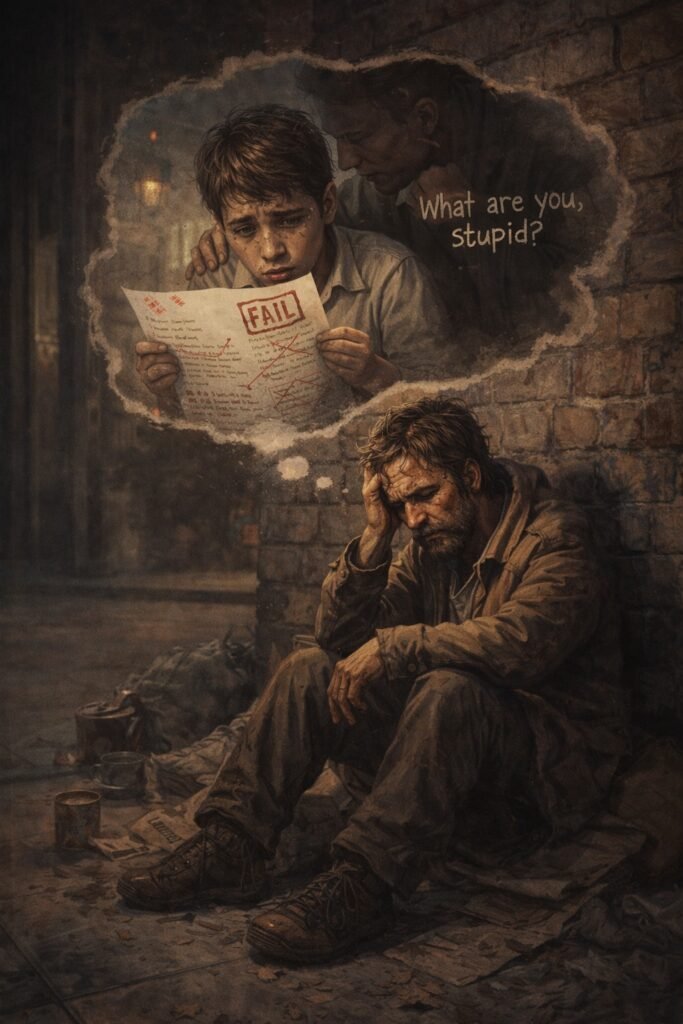

they don’t just measure performance—they train you to outsource your sense of worth.

They feel neutral and necessary. That’s exactly why they’re dangerous.

Grading is a necessary evil in education. Necessary, because institutions require some way to sort, credential, and move people through systems at scale. Evil—not in a melodramatic sense, but in a quiet, corrosive one—because grades are so easily mistaken for something they are not.

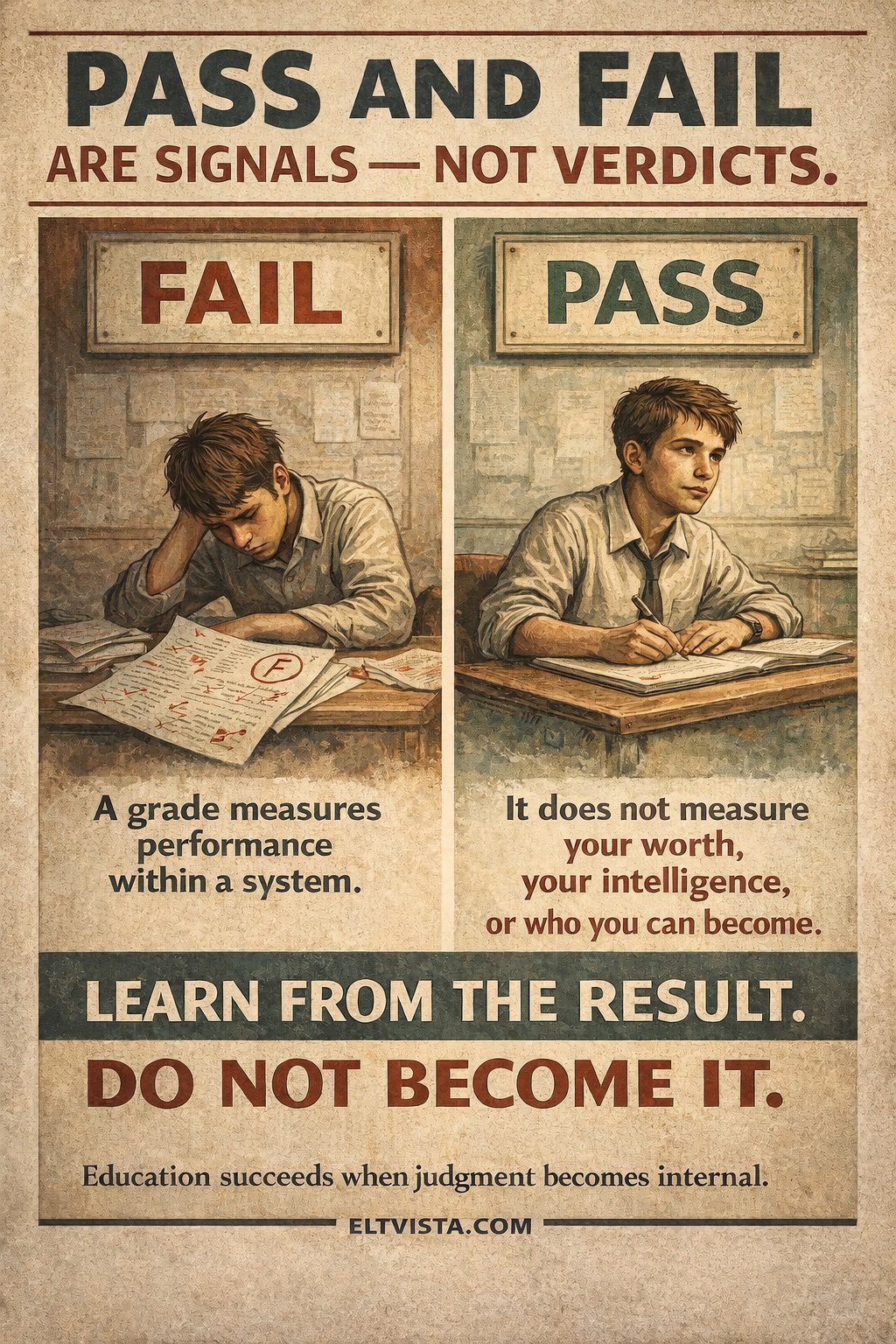

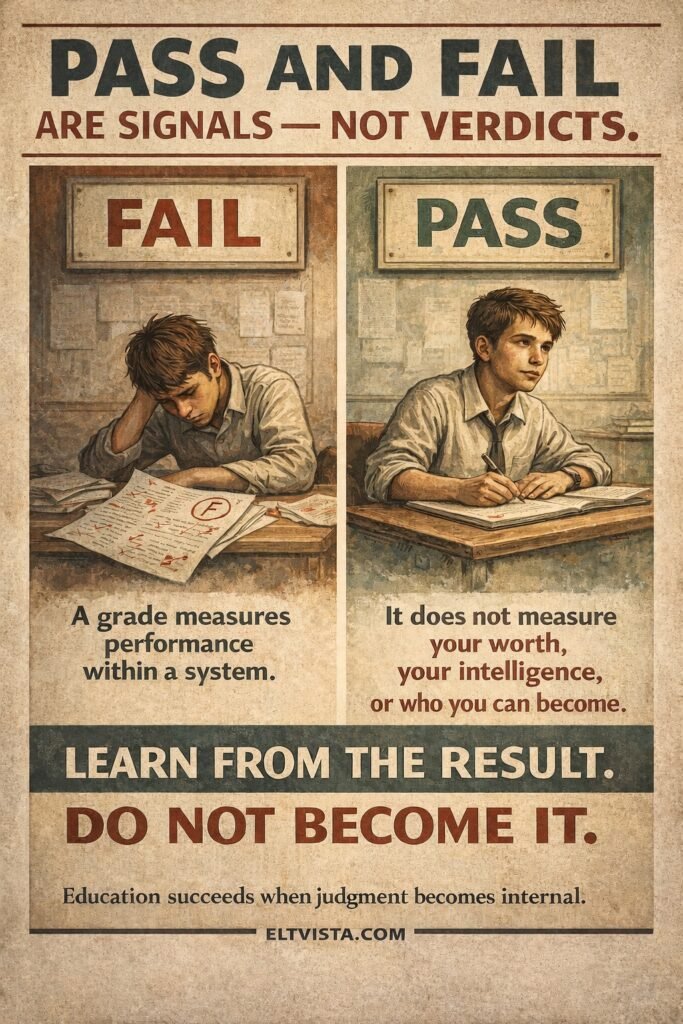

A grade is information. It is a signal within a bounded system. It is not a measure of human worth, potential, or legitimacy. Most students are never explicitly told this, which is why the signal so easily becomes a verdict. Unless that caveat is made explicit, students absorb something far more dangerous than the grade itself: the idea that judgment arrives from elsewhere, and that its verdict is final.

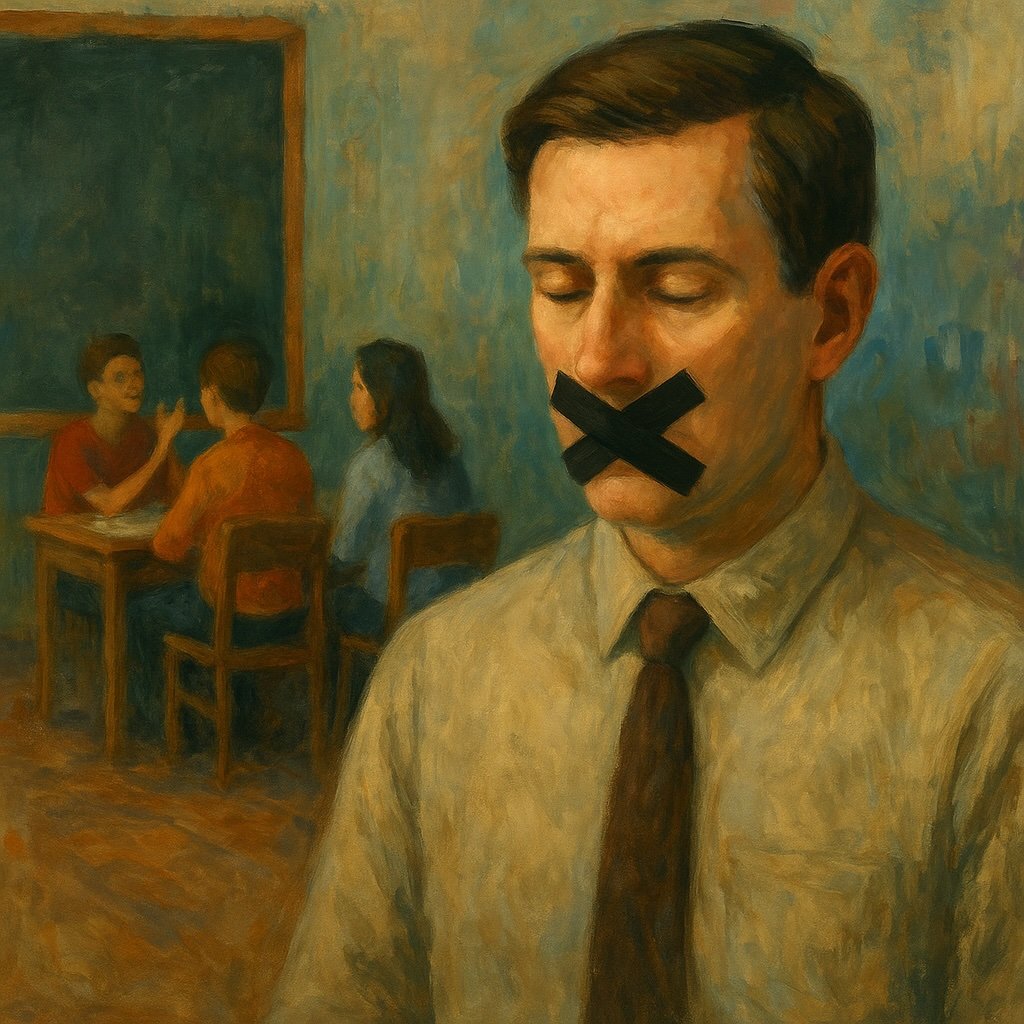

This is where the real injustice begins. Not because the system is intentionally cruel, but because it is largely silent about what its judgments are meant to mean—and what they are not.

From early schooling onward, students learn to wait. They wait for the number, the letter, the rubric score—for the rules that define what is allowed and what is not. Over time, the question subtly shifts from How did I do? to What does this say about me? If this feels familiar, it’s because most of us were trained this way long before we knew to question it. When that shift goes unchallenged, education stops preparing people to participate in society as autonomous agents and starts preparing them to function as compliant units within it.

The image that comes to mind is not flattering, but it is apt. The comparison is uncomfortable, and that discomfort is part of the point: rats in a maze, pushing the lever because the lever once produced a reward. Not because the action has meaning, but because it has been reinforced. If you have ever caught yourself waiting for permission to act, you already know how effective this training can be.

Behavioral conditioning explains a great deal about how learning works, particularly at the level of habit formation. The issue isn’t how habits form, but what happens when habit replaces judgment. When an explanatory model becomes a totalizing philosophy of education, students may become efficient—but they do not become free.

And education, at its best, has always been about more than efficiency. Most people sense this intuitively, even if the system rarely rewards it.

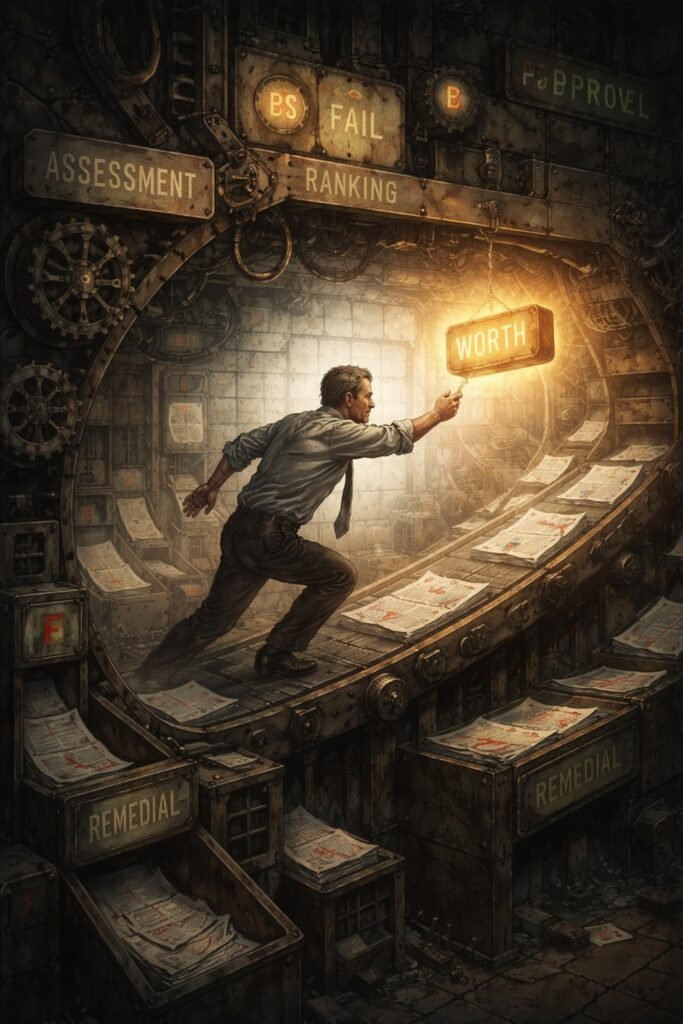

What’s happening in classrooms mirrors something much older and much broader than schooling. Grades are only one visible cog in a larger mechanism—one that long predates formal education. It is the machinery of deference, legitimacy, and external authorization. Schools did not invent it. They merely normalized it early and often, shaping a prefabricated sense of what counts as acceptable, possible, or “good enough.”

The tragedy is that this mechanism does not end at graduation. It simply changes costumes. For many, it becomes harder to see precisely because it feels normal.

On social media, the lever becomes the “like” button. The post with the most engagement wins. Visibility is mistaken for value. Popularity masquerades as legitimacy. Most of us have felt the small jolt of validation—or disappointment—that comes with that count. Everyone is invited—quietly but relentlessly—to audition for relevance.

Why the obsession with fame? Why the fixation on celebrity? Why entire media empires devoted to watching other people be watched? These questions linger because the system trains us to seek confirmation before meaning.

Outlets like TMZ, glossy covers of Time, awards, rankings, viral moments, blue checkmarks—these are not trivial cultural artifacts. None of this is accidental; it rewards the same reflex students first encounter in graded classrooms. Someone else will tell you what matters, and you will know you have arrived when they do.

Even our highest honors—the Nobel Prizes, the hall-of-fame inductions, the “top” lists—operate within this framework. Recognition itself is not wrong. Judgment is not avoidable. Recognition becomes dangerous only when it replaces self-trust.

This is where the original critique often misfires. Judgment itself is not the enemy. The absence of inner judgment is.

This distinction matters, because without it reform collapses into resentment. When people are trained to rely on external evaluation without developing the capacity to judge for themselves, choice ceases to feel like freedom. It feels like paralysis. You can see this when capable people freeze without permission. Without a cultivated sense of discernment, responsibility becomes overwhelming. Decisions feel illegitimate unless rubber-stamped by authority—whether that authority is a teacher, an algorithm, a crowd, or a credential.

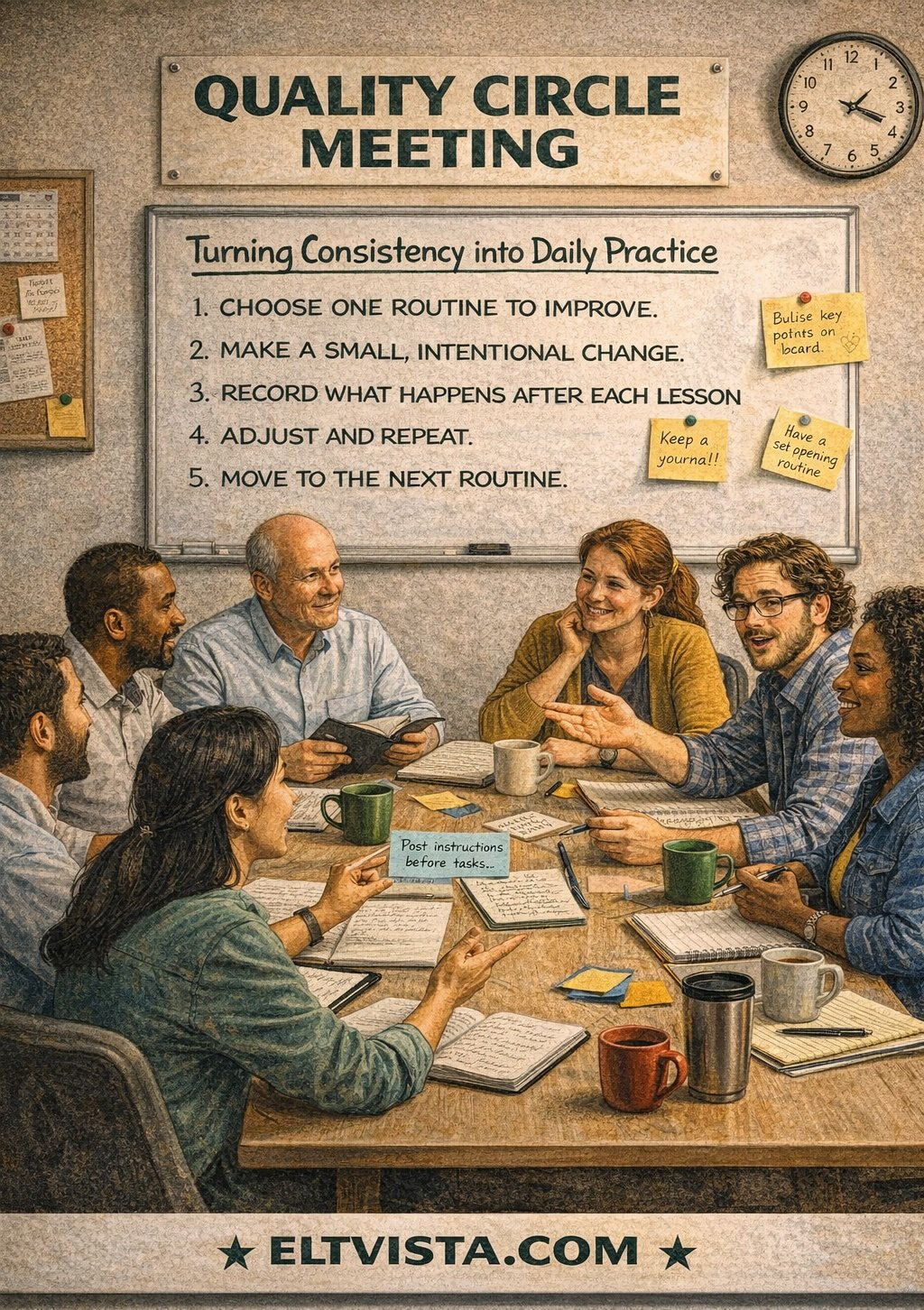

Long before algorithms and dashboards, educators noticed this problem. John Dewey, an American philosopher and educational reformer, argued that education should not merely transmit knowledge but cultivate reflective judgment and democratic participation. Likewise, Lev Vygotsky, a Russian psychologist known for his work on social learning, emphasized that learning is social—but never meant that individuals should remain dependent on external scaffolding forever. Scaffolds are meant to be removed. Otherwise, growth stalls.

From a humanistic perspective, the goal of education is not obedience, nor even competence alone, but character: the ability to weigh, to choose, to stand behind one’s decisions, and to revise them when necessary. This is less about ideology than about what kind of adults education produces.

This is where my book What About the Teacher? inevitably enters the conversation—because this problem does not begin, and does not end, with students.

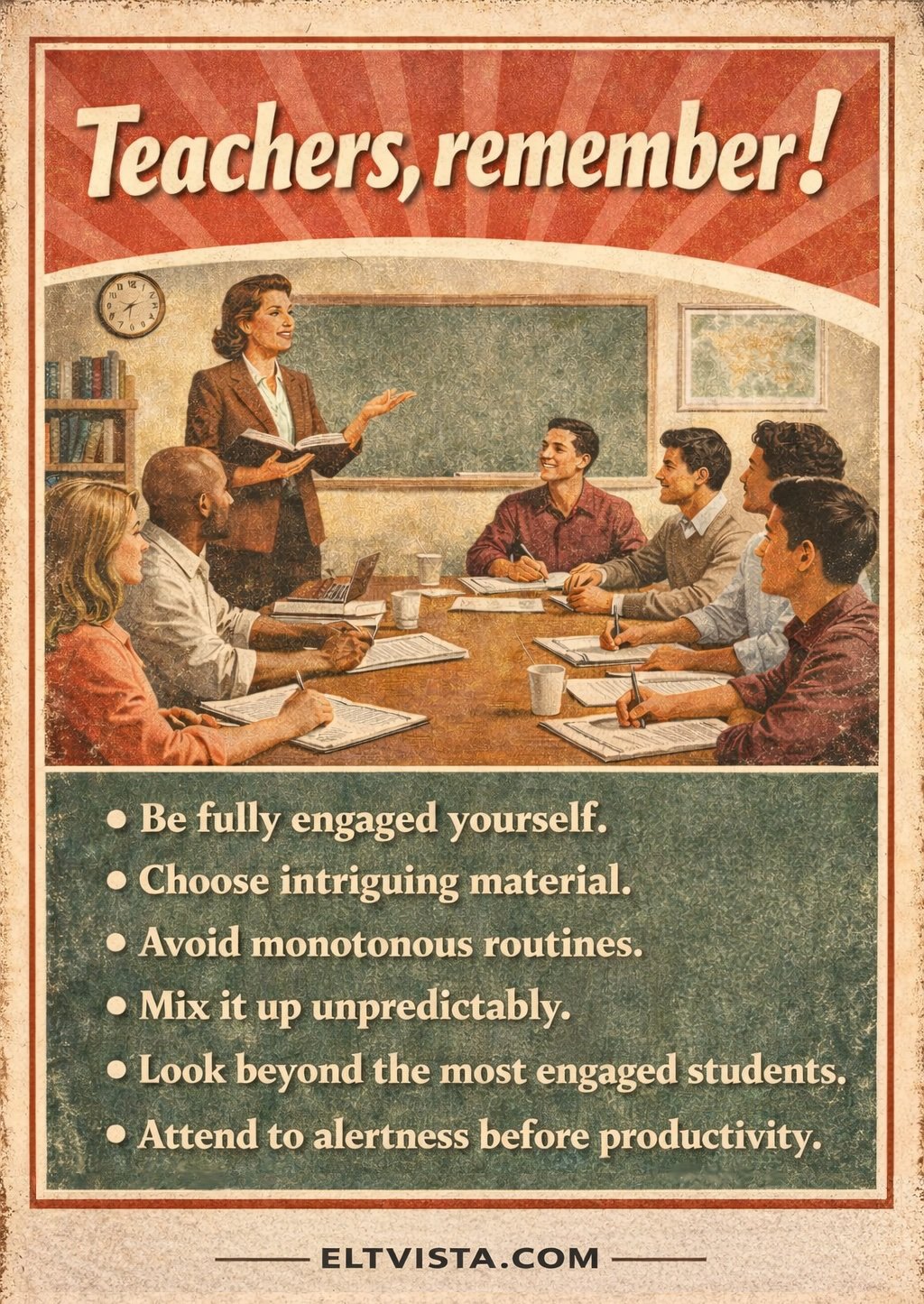

If teachers themselves have never been encouraged to examine their own relationship to authority, legitimacy, and evaluation, they will unconsciously reproduce the very patterns they wish to dismantle. Most of us were trained inside the same system we now question. We cannot model self-actualization while secretly waiting for approval. We cannot teach discernment while outsourcing our own.

The real task, then, is not to abolish grades, systems, or judgment—fantasies that collapse under their own idealism. The task is far more demanding: to teach students, and ourselves, what grades are, what they are not, and when they cease to matter.

Education fails when it trains compliance without consciousness. It succeeds when it helps people recognize the box for what it is: not natural, not inevitable, but assembled. The moment someone sees the box clearly, its grip begins to loosen.

The measure of a good education is not how well students perform in the maze—but whether they eventually learn to step outside it.

If this question feels familiar, it’s one I return to often—here, and throughout my work at ELT Vista.

For more articles like this, please consider our publication, What About The Teacher?—the main text upon which the our online certificate course in humanistic TESOL teaching is based. The book is available online in both digital and paperback formats at: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0FPBWNXTZ

✨ While you are contemplating your personal and profesional development, as well as your New Year’s resolutions, please consider adding our self-paced 120-hour online certificate course to your list: For more information, click here for the ELT Vista Certificate in Humanistic TESOL Teaching. Enrollment Is Open Now with a special! Holiday Launch promotion! ✨